A New Look for Jiri Prochazka

Jiri Prochazka provided the most pleasant surprise on the UFC 311 card. After Alex Pereira and Aleksander Rakic low kicked him with impunity in three back-to-back fights, it was clear that Prochazka was struggling to assess and address his shortcomings. Against Jamahal Hill he avoided a couple of low kicks (though Hill only threw a couple), and showed something altogether new.

Prochazka has always switched stances in his fights, but it was always on a whim. He switch hit in the same way most MMA fighters do: 90% from the stance he trains in all day, and a couple of tricks from the opposite stance, never lingering because he was not defensively comfortable. Against Hill, Prochazka showed a fresh new look: using his southpaw stance as a base from which to counter.

That in itself would be moderately tricky, but Prochazka went a step further and worked to hide his shifts into southpaw. He would stand orthodox the majority of the time, then shift through to southpaw during an exchange, and then counter with the new weapon opened up from there. Figure 1 shows Prochazka retreating from a Hill jab (a), stepping back into southpaw (c), then slipping off to his left (d) and returning with the open side counter (f).

Fig. 1

On offence he primarily shifted into southpaw after throwing a long right straight and falling forwards. It was the classic Poirier Shift that we examined at length in Advanced Striking 2.0 - Dustin Poirier.

If Hill did not give ground to allow the shift to southpaw, Prochazka would either shoulder bump him back or grab the double collar tie and throw knees as in Figure 2.

Fig. 2

Figure 3 shows a perfect example of Prochazka’s best work. He fakes with his head as he switches his feet (b). As Hill attempts to come back, Prochazka slides back to his left (c), (d), and answers with the open side counter which narrowly misses.

Fig. 3

While Prochazka had found a good idea, his approach became one-note after the first round. He would throw a long right straight, shift through, and then bounce back hoping to counter as a southpaw. It was becoming more difficult to get Hill to fall for it and commit. Then in round three, Prochakza found his greatest success by more aggressively extending the exchange. Figure 4 shows the trick.

Jiri throws fakes a right hand (b) and throws a right round kick to the body (c). He places the kicking foot down to advance into southpaw, throws a left straight, and keeps Hill under pressure (d). Hill circles off and Jiri pivots to face him (e).

Fig. 4

Figure 5 picks up the action. As Jiri pursues Hill, Hill digs in on a southpaw jab, which Prochazka slips (f). Prochazka returns with the counter left hand across the top, stiffening Hill’s legs (g).

Fig. 5

The knockout a minute or two later, came as Prochazka increased the pressure on Hill, and Hill fought back in earnest. The same southpaw left hand counter appeared in an exchange, followed by a right hook that sent Hill to the mat for the finish.

While this fight did not suggest for a moment that Prochazka now has an answer for Alex Pereira, the addition of this one punch to his game is a breath of fresh air. Not only is it a new look but it is one that benefits most from being attached to the berserker strategy for which Prochazka became famous. As Conor McGregor’s entire career showed: the open side counter is at its finest when an overwhelmed opponent desperately pops their head above the parapet to take a shot back.

A Rare Breed of Heavyweight Banger

The fight between Jailton Almeida and Sergey Spivac did not last long, but it delivered in a way few heavyweight fights do. To borrow from pro wrestling parlance, the big lads “got their shit in.” Spivac hit a beautiful judo throw, Almeida swept, Spivac reversed, Almeida scrambled up, a couple of punches were thrown and that was the lot.

A key feature of this fight was the Lucas Leite style half guard. If you had to build a bottom game from scratch, the Leite guard / coyote guard is more than enough. This is the original “wrestle up”. Figure 6 shows a typical example. The key is that Almeida has the underhook on the same side as his half guard, and his outside leg (his right leg) is hooked over the top of Spivac’s calf.

Fig. 6

Figure 7 shows an important adjustment that makes this all possible. Almeida begins in half guard, and has an underhook with his right arm. He has sat up into Spivac but Spivac is sat on his own heels (a). Almeida uses his right foot on the mat to pull his butt in underneath Spivac (b). This throws Spivac forward onto his hands, bringing his butt off his heels (c). This allows Almeida to throw his right foot over the top of Spivac’s left calf (d).

Fig. 7

In frame (e) you can see that Almeida has the right underhook, his right foot over the top of Spivac’s lower leg, and his left hand scooped behind Spivac’s right thigh.

But this was not just a Jailton Almeida jiu jitsu demonstration. Spivac is about as competent as heavyweight grapplers get. As you can see in Figure 8, Spivac immediately slammed a forearm underneath Almeida’s jaw (b) and straightened him out. Almeida retracted his left hand from behind Spivac’s thigh and parried Spivac’s elbow over his head just long enough to dive back in on Spivac’s legs, grabbing Spivac’s right foot which had drifted too close (d). This enabled Almeida to pull himself up into Spivac and simply topple the big Russian over (e), (f).

Fig. 8

The Leite / coyote guard normally involves wrestling up to your knees. For this reason, elite jiu jitsu players have shown it might be the one useful guard pull for MMA. Demian Maia and Rafael Lovato had great success with it against good fighters. Here is Kleber Koike Erbst sitting in underneath Chihiro Suzuki and wrestling his way up into bodylock takedown.

Fig. 9

Fig. 10

But the moment the bottom fighter hits his knees, this is more “wrestling” than it is “guard.” It is the so-called “dog-fight” position and the reversal is not anything close to guaranteed. On the undercard of UFC 311, Ricky Turcios repeatedly got up to his knees from the Leite guard and then lost his opponent in the scramble.

There are a few options where the bottom fighter uses torque on the knee to force a backstep and Erbst demonstrated a seldom seen “leg bundle” sweep against Suzuki—locking his legs around Suzuki’s thighs so that Suzuki was forced to fight for his balance with just his hands.

Fig. 11

In the Almeida - Spivac fight, Spivac was doing a decent job at preventing Almeida from building up to his elbow or getting underneath him, but in the hurly burly he let his right foot come too close underneath his own butt and gave Almeida the clean shot at Eddie Bravo’s “old school” sweep. Because Spivac’s foot was so close underneath his centre of gravity when Almeida grabbed it, he had no hope of sprawling out of the control or basing out on it when Almeida sat up into him.

And it would be a shame to end this article without giving some praise to Derrick Lewis, who did not fight at UFC 311 but who was proven correct by Spivac. When Lewis is mounted, he immediately turns his back in the way that you are told not to from day one.

Fig. 12

In the course of this he grabs his opponent’s hand (so that they cannot quickly choke him), and then rolls through. From a grappling perspective, Lewis has just pulled his opponent onto his back. From an MMA perspective, he has just removed all of his opponent’s striking options and placed himself on top of them. All that is left is to turn back into them.

Fig. 13

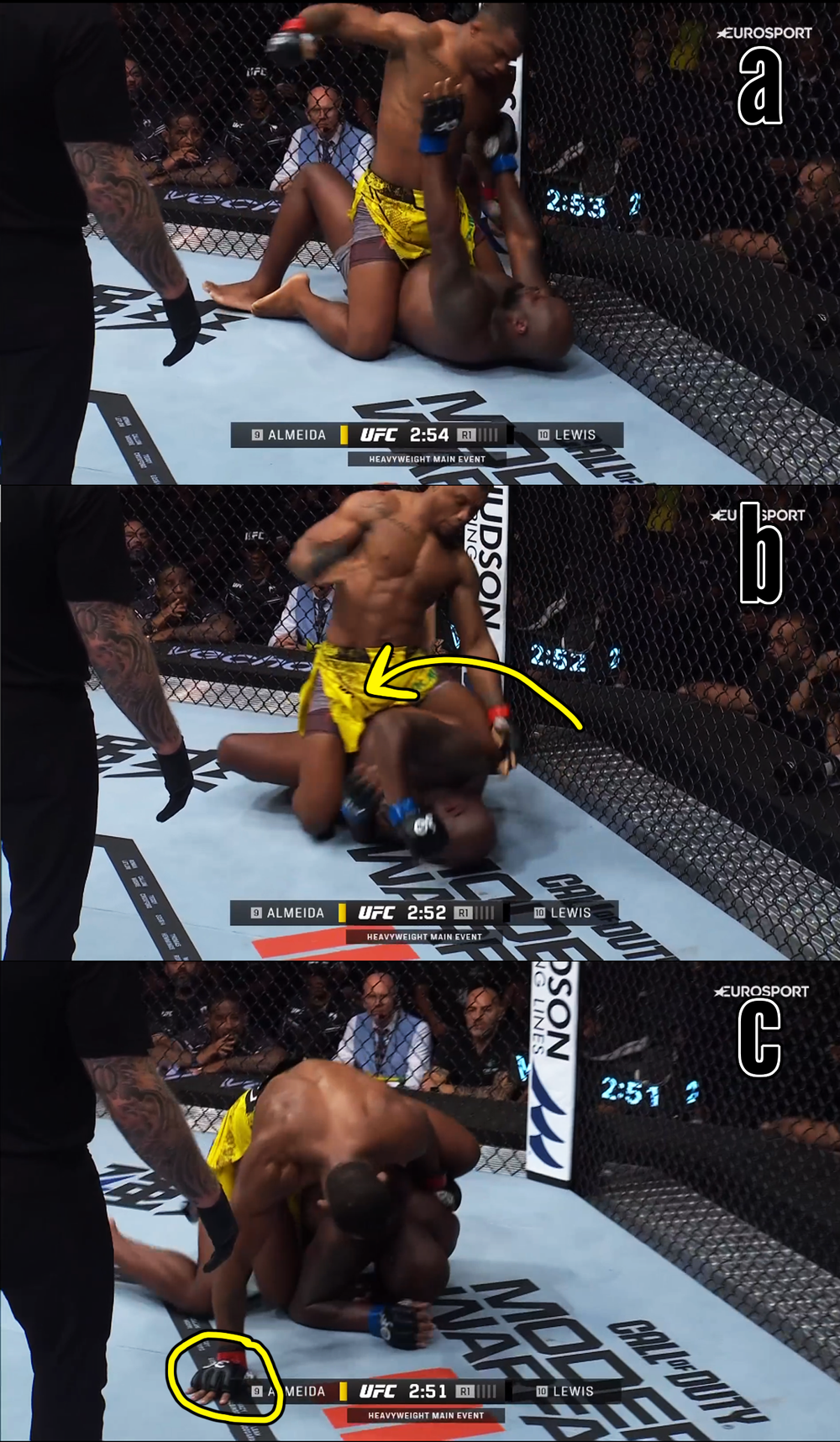

When Almeida mounted Spivac, Spivac waited for Almeida to posture up and then he did the very same thing.

Fig. 14

Once he was safely on top of Almeida, it was just a case of separating Almeida’s hands, whipping the choking hand over his head, and turning back into Almeida.

Fig. 15

The rear naked choke is a very real threat, but it is a lot easier to see coming than a quick punch or elbow from the mount with 260 pounds of beef behind it.

If you’re all grappled out and just want to read about hitting people, check out my recent striking-heavy articles on Yothin, Carlos Prates, or Yuki Yoza.