Advanced Striking 2.0 -

Alex Pereira

While the Ultimate Fighting Championship is needlessly exploitative in its pay structure, the purses available for a great fighter in the UFC still far outweigh those in most promotions and combat sports. For this reason dozens of great kickboxers have teased the idea of—or even attempted—jumping ship from their own sport to mixed martial arts. Perhaps the most glaring example of this is Alex Pereira.

Pereira is one of the finest kickboxers of his generation: a two-division world champion in Glory, who knocked out the majority of those who fought against him, and yet kickboxing’s premier company could not muster the money to prevent him from departing to attempt an MMA career for which he was far less prepared. Pereira was helped in his transition by the fact that his old rival, Israel Adesanya, had successfully become the UFC middleweight champion and their pre-existing rivalry and Pereira’s highlight reel knockouts led the UFC to line up opponents who posed little threat of taking Pereira down or making the bouts into mixed martial arts contests. At the time of writing, Pereira is scheduled to fight Israel Adesanya for the UFC middleweight crown at UFC 281 in Madison Square Garden, but this study will focus rather on Alex Pereira the kickboxing sensation.

Fig. 1

The Pure Left Hook

Had Alex Pereira never developed anything but his left hook he might still have found seventy or eighty percent of his current success: such is the potency of the King of Counter Punches. The young Poatan cut his teeth in boxing before transitioning to kickboxing, and a repeated criticism from his peers (often shortly before or after he knocked them out) was that Pereira was just a boxer playing kickboxing. It was a criticism that hearkened back to the days of American long-pants kickboxing, where low kicks were outlawed and fighters found it easier to slug it out, so minimum kick tariffs had to be set for each round to prevent the sport from simply becoming bad boxing. But these critiques of Pereira seem to be a sour grapes response to the reality that every kickboxing match eventually sees a trading of blows in punching range, and a world class left hook is a chance to finish or at least severely alter the fight in every of these trades.

The beauty of Pereira’s left hook comes from what Jack Dempsey would call “punching purity.” That is to say that on Pereira’s best hooks his weight is moving into the force of the blow, and despite his lengthy build he loses little power in excess motion or looping of his shot. For the most part taller fighters tend to get in the habit of whipping their hooks and throwing them extremely wide, but Peireira has the left hook of a shorter, more compact man.

Even among accomplished hookers, many left hooks run contrary to this idea of weight transfer in the direction of the blow. Most left hookers attempt to advance and throw the hook at the same time. The general rule is that to get his weight into a blow moving from left to right, a fighter must shift his weight from his left foot to his right foot as he turns his body. But a fighter only has two feet: the right foot is also the rear foot. So to throw a truly “pure” left hook the fighter must transfer his weight to his rear foot, which is difficult to do when attempting to advance.

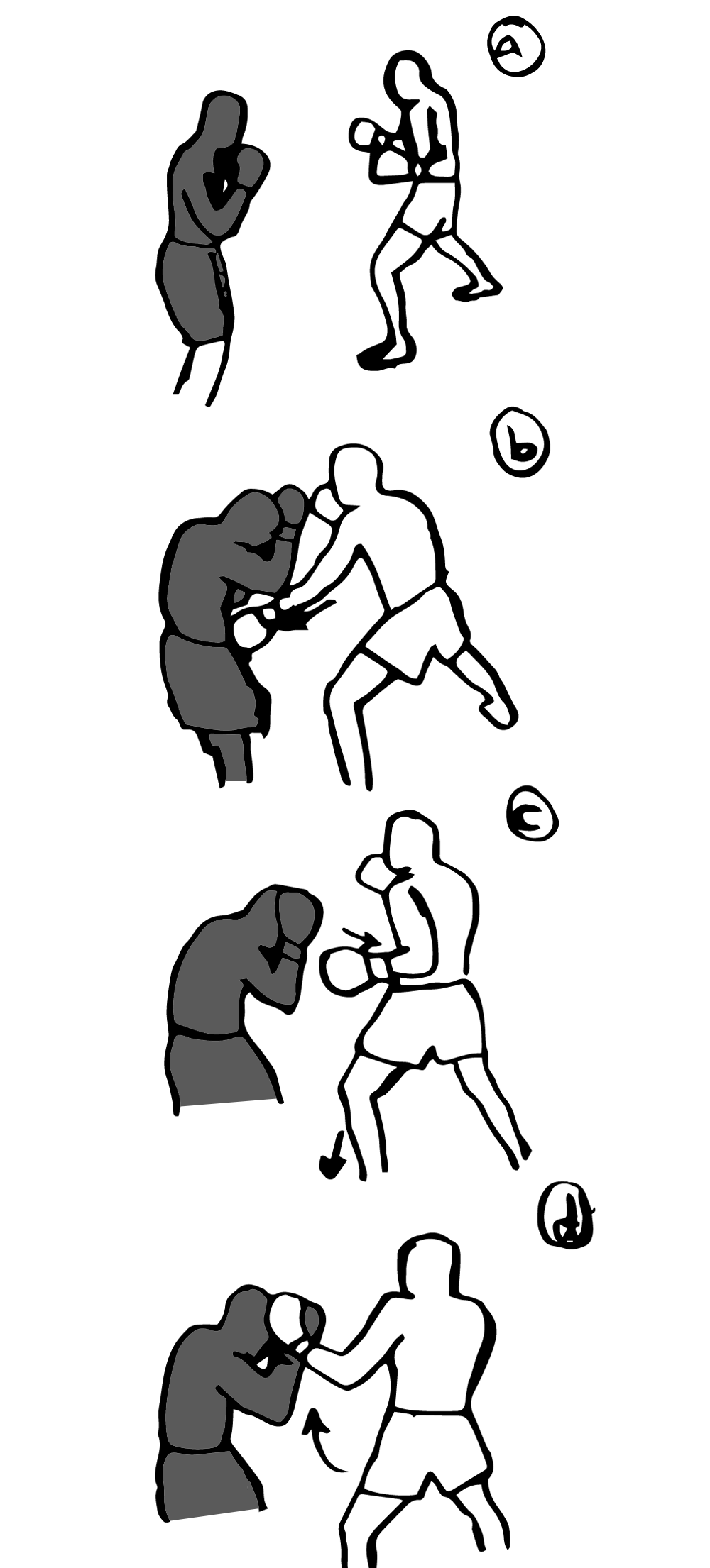

Figure 2 shows the footwork that Pereira uses to create colossal force in his counter left hook. His right foot will retreat half a step, dropping his weight back and towards his right as his hips and shoulders whirl into the blow. In kickboxing, pivoting on the lead foot when hooking is discouraged because it makes the fighters lead leg vulnerable to the low kick, but when enticing his opponent onto a counter hook, Pereira pivots to an almost side on position.

Fig. 2

Yet anyone who has seen even a couple of heavyweight boxing matches can tell you that a good hitter can comfortably knock a fighter out with an advancing or leaping left hook. In fact Pereira himself swung wide around Sean Strickland’s reaching right hand with a leaping left hook to score the KO, but the point is that in an advancing left hook a lot of potential power is being left on the table. Often leaping left hooks are thrown wider at the shoulder to make up for the power lost with the feet being otherwise occupied (or off the mat altogether.) Most of Alex Pereira’s best left hooks are landed as he slides back or returns to his stance after throwing his right hand. While this means that his weight is being transferred to his right foot and his punch has that “purity” it looks surreal to throw knock out shots while fading away, and this has aided Pereira’s reputation for having a spooky, one-in-a-lifetime sort of power.

One way that this backwards moving power can be applied is seen when Pereira stands in front of his opponent with his gloves at shoulder height and wide apart creating a window for the opponent to shoot through. As his opponent shoots a right straight or a jab, Pereira steps onto his right foot and whips the left hook across the top, turning almost side-on in the process. While Pereira might have perfect “short man” left hooking form, being a 6’4” middleweight fighting men who are 5’11” unarguably gives him an edge in using his left hook to cross over the top of the opponent’s right hand.

Another feature in the mechanics of Pereira’s hook is that rather than trying to hit the opponent with his hand as hard as he can, his technique is mainly about the path of his elbow. As he whirls his shoulders his elbow comes to the centreline and his hand blasts through the target as a happy side effect of being attached. This stands in sharp contrast to many fighters who allow their elbow to fly far from their body or drop low as they focus on slapping the opponent with their glove.

As Pereira developed a kicking game, he built it with the intention of remaining in position to score the counter left hook. He would, of course, try to score a cheeky wheel kick knockout from time to time, but the meat of his kicking game was designed around scoring and using the weight transition of returning his kicking leg to the ground to generate power on the counter left hook. Figure 3 shows a typical example of Pereira using a naked low kick to draw the opponent onto a counter left hook. There are a hundred styles of kickboxing but this kick-to-counter is the complete inverse of the traditional Dutch template of rapid punching in order to score the close range, fully committed low kick.

Fig. 3

In complete contrast to the damage focused low kick that ends combinations in kickboxing, Pereira holds his right hip back (b, c), resulting in an upward slanted kick that never turns over in the traditional power kicking style. Where his hooks are about getting as much weight as possible into the blow and achieving that “purity” of punch, his kicks are designed to commit as little weight as possible. Just as with the idea of punching purity in the left hook, holding back the hip does not prevent a kick from packing a wallop, it just leaves a lot of potential power on the table in service of maintaining position. Crucially, even a cautious right low kick transfers the fighter’s weight onto his left foot, and as the right foot is returned to the mat he can time the left hook with a transfer of weight to the rear of his stance.

Once Pereira had acquired a reputation for counter hooking—and left a few good opponents face down off their charges—the low kick often wasn’t enough to draw out the kind of reckless exchange he wanted from his opponents. The high kick proved a far more effective method of creating frantic action and can often be seen in Pereira’s fights setting up the left hook as in Figure 4 . Seasoned fighters seem better at stifling their instinct to “get one back” on low kicks than when a shin bone smashes their forearm into the side of their head and puts them in a panic. This seems true at all levels as Pereira used the same high kick to panic and counter the regional MMA talent, Thomas Powell and the kickboxing world title challenger, Donegi Abena.

Fig. 4

Another way in which a fighter can get weight into the left hook is to play off the relationship between the lead hand hook and the lead hand uppercut. In Dempsey’s rules—laid out in Championship Fighting—a pure left uppercut involves squaring the stance and driving up off the lead foot: the bodyweight is put into motion behind the blow, upwards.

Figure 5 shows one way that Alex Pereira applies this is in a C-cut combination. Pereira pitches an overhand on a covering opponent (c), encouraging them to stoop or even move into him, and then shortens his stance by bringing his back foot up (d). From this shorter, more squared stance he can drive his body weight up off his lead leg and across onto his right foot. The left uppercut has been a constant weapon for Pereira against shorter opponents to punish or deter them from ducking into his chest.

Fig. 5

Another way in which Pereira uses the left uppercut is to shoot the right straight to his opponent’s solar plexus, changing levels in the process, and use the left uppercut to return to an upright position. This left uppercut forces most opponents to reconsider level changing and fight more upright, meaning that Pereira can use the same entry—a right straight to the body—to set his feet for a left uppercut, but instead let his elbow flare out and his shoulders whirl to his right and throw a powerful, rising left hook. In the fifth defence of his Glory middleweight title, Pereira made quick work of Ertugrul Bayrak with this set up along the ropes.

Fig. 6

All of this focus on the “pure” hook is not to say that Pereira does not use “impure” hooks. He throws left hooks while advancing or bouncing forwards in all his fights, sometimes as slaps and sometimes as genuinely stiff blows. This brings us onto the relationship between the knee and the left hook. A slapping left hook is quickly turned into a check on the opponent’s right glove and ensures the correct distance for a right stepping knee. More than any other “kickboxing” strike, the right knee has become a vital element of Pereira’s game and allows him to punish his opponents’ kickboxing instinct to “put on the earmuffs” with their gloves when he throws his punches. Figure 7 shows the slapping left to set a right knee to the body, but because of his height Pereira has also found success throwing the right knee to his opponent’s face.

Fig. 7

While the left hook feeds perfectly into the right knee by setting the correct distance and priming the opponent’s double forearms defence, the right knee also feeds perfectly into a powerful left hook. After the knee has landed, the fighters must move apart to strike effectively and so Pereira will return his right foot to the floor behind him, not only carrying him back from a clinch striking range to an exchanging range, but performing that same weight transfer that allows Pereira to whirl his hips and shoulders with such force. Pereira smoked Dustin Jacoby with this right knee to left hook combination in his early Glory career.

A final carry-over from boxing that makes Pereira an oddity in kickboxing is his body jab. His length means that he can drive in a jab well to the head or the body, and the squared stance and high guard that are so common in kickboxing present him with the solar plexus as a target almost constantly through a match. Pereira will attack the body jab, and then roll down behind his lead shoulder to deflect or evade a returning right hand. This ducking down behind the shoulder is something that allows Pereira to stay in range and continue punching, but was also used against him by Artem Vakhitov.

The upside of using the body jab is that Pereira has a weapon in his arsenal that doesn’t exist for most kickboxers, and it can set up combinations—such as the body jab to side step and left hook (which in turn can set up a right knee) in Figure 8. Moreover, the body jab can be played in a double attack with the jab to the head: the simple act of showing the body jab from time to time makes it easier to pot shot with single jabs to the head from the outside.

Fig. 8

The key flaw of the body jab is one that every kickboxer is aware of, and the reason that so few use it. To score an effective, long range body jab a fighter must change level and extend his stance into a bladed position, making him vulnerable to low kicks. Many of Pereira’s opponents have been able to time good low kicks on him in the aftermath of a body jab, but he seems to have simply accepted that as a risk of attempting the technique and continues to have success with it nonetheless.

Fig. 9

Most recently Pereira used the body jab to draw forward Sean Strickland’s right hand. Strickland has always loved reaching for his opponent’s jabs, but with the cajoling of the body jab Strickland’s right hand was down by his nipples when Pereira leapt into the left hook knockout shot.

The Rivals

Alex Pereira’s career has been defined by a series of rivalries. In a relatively short kickboxing career, Pereira fought pairs of fights against Israel Adesanya, Simon Marcus, Artem Vakhitov and Cesar Almeida, and trilogies against Jason Wilnis and Yousri Belgaroui. Against all but Vakhitov, Peireira had the last laugh, and while the counter left hook was the bread and butter of Pereira’s game his adaptations to different styles, particularly opponents he had encountered before, marked him out as the elite competitor that he was.

Simon Marcus

Simon Marcus was the man holding the Glory middleweight crown when Alex Pereira finally got a crack at it in October 2017. While Pereira would later find that he could not make the money he desired in kickboxing, Marcus had a similar experience fighting as a middleweight and light heavyweight competing under Muay Thai rules. Marcus’ greatest asset was his clinch work and yet, to get fights and to make ends meet, he was forced to fight in a kickboxing organization, under a ruleset that denied him much of his clinch arsenal.

In their first meeting, Marcus relied heavily on his textbook left switch kick to the body, before pitching overhand swings and falling into the clinch. Glory rules originally permitted a single knee strike from the clinch before the referee broke the fighters, but eventually settled on “up to five seconds” if one fighter was actively striking for the duration.

After a closely matched first round, Pereira found his mark in the second. By bowling a wide overhand, Pereira could encourage the shorter clinchophile to duck into his chest. After baiting the trap with a couple of earnest overhand swings off which Marcus clinched, Pereira showed the overhand again and then heaved a colossal left uppercut through the space between his chest and Marcus’. Marcus stumbled for only a millisecond and played it off well, but—crucially— he stopped committing to the action that got him hurt: he stopped ducking in. As Pereira closed in on him, Marcus stood upright and chucked an overhand of his own and Pereira slipped to his left and nailed the Canadian champion with a right down the pipe that dropped him to the mat. It was a round from which Marcus never recovered and Pereira sailed to a victory on the scorecards.

One rule has been a constant in Alex Pereira’s career: when he meets an opponent a second or third time, he fights more aggressively than the last. When Marcus and Pereira met for a rematch, a year removed from their first title fight, Pereira piled on the offence from the opening bell. Where the left uppercut was a trap he carefully set and then committed wholeheartedly to in the first fight, it was a constant annoyance in the second. Pereira focused more on straight hitting with ones and twos, and ended most of his combinations with left uppercuts to keep Marcus upright and in the firing line.

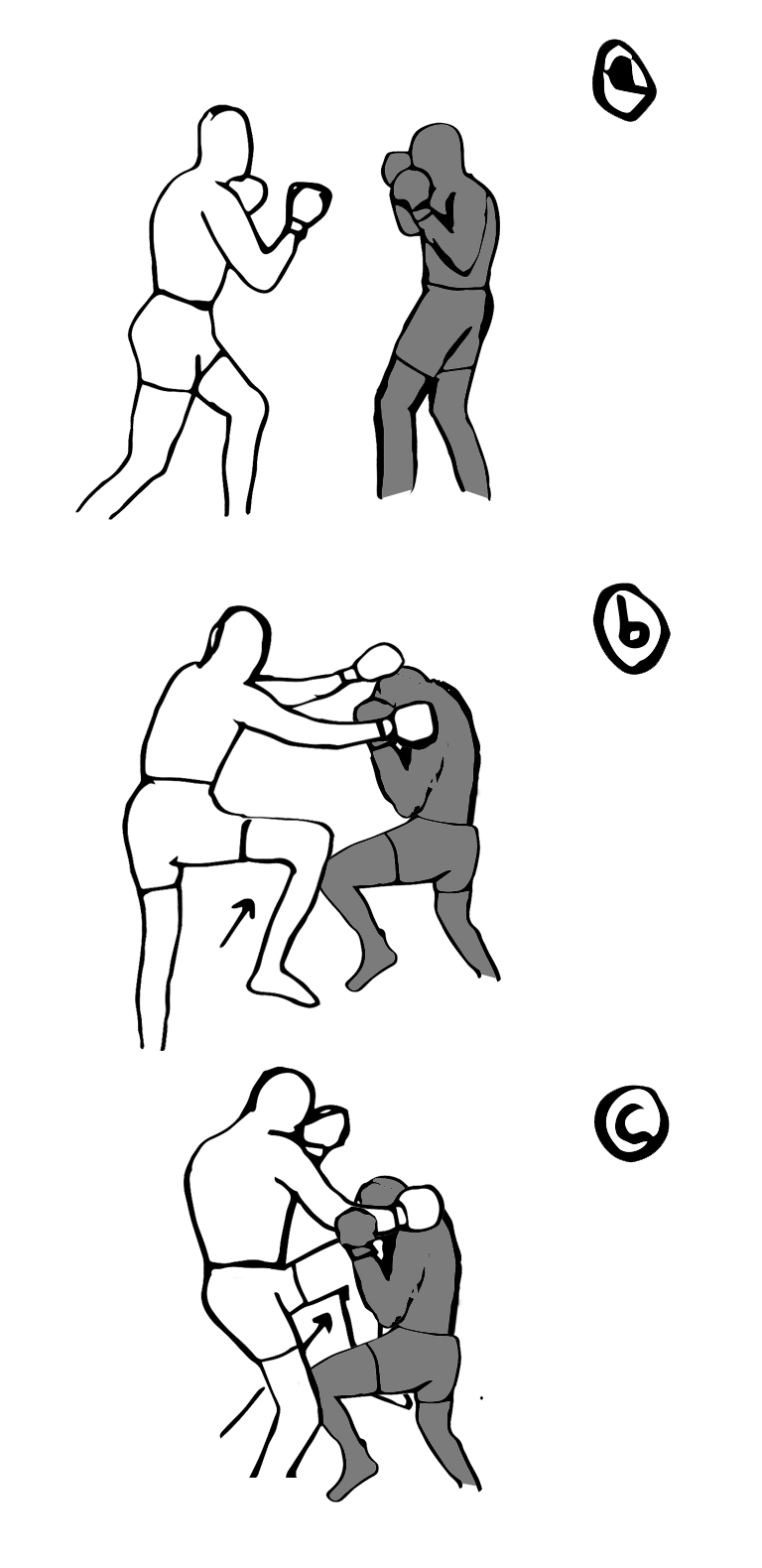

Marcus’ chances rapidly diminished as it became apparent that Pereira had worked out the clinch since the last time they fought. Where Marcus had snuck in some good knees in their first meeting, Pereira denied him with a severe frame across the body with his knee. Figure 10 shows how Pereira held his left knee across Marcus’ far hip, rendering both of Marcus’ knees ineffective. The obvious flaw of this position is that the fighter using the cross check with his knee has no balance. Were it a Muay Thai match, Marcus would sling him to the floor effortlessly. But the rules of Glory permit a little clinch striking and no throws, sweeps or dumps. The moment that Pereira placed his knee across Marcus’ belt line, Marcus was completely shackled.

Fig. 10

Jason Wilnis and Artem Vakhitov

Of all Alex Pereira’s rivalries, that with Jason Wilnis best encompasses his growth from boxer to kickboxer. The first time that Pereira met Wilnis was in 2012, after only a little success on the Brazilian regional scene. Pereira lived and died by his punches, and Wilnis was happy to let Pereira get into range to hit him. Then, as now, Wilnis was determined to absorb blows on his gloves, forearms, or skull, and return with powerful low kicks from close range.

The beauty of the Wilnis’ method is that if the opponent is close enough to punch your guard, you know that you are close enough to land low kicks. You also know that his feet are likely set for a moment after his punches connect and he isn’t in the best position to pick one leg up and check the kick. And this was compounded by Pereira’s punching form. Most elite kickboxers will not pivot on their lead foot when they throw a left hook, or go into a bladed stance to jab, because these actions present the back of the lead leg and turn the punchers shin and quadriceps away from the direction he needs to check in. Pereira pivoted passionately into his punches and simply wasn’t ready for the level of punishment Wilnis would impart on him for doing this.

Pereira found no resistance to his closing the distance to punching range from the opening bell so he waltzed right up to Wilnis and started swinging. Then when he ended his combination, he felt his knee get buckled inwards by the Wilnis low kick. This sequence played out repeatedly and Pereira found himself in a confused position: standing in front of Wilnis with no work needed to close the distance, but also reluctant to open up. He began halfheartedly tapping at Wilnis’ guard rather than unloading big blows, but the low kicks came in just the same. After being severely hobbled by this build up of low kicks, Pereira was a sitting duck for a picture perfect liver shot that put him out of action.

Pereira and Wilnis met a second time three years later in 2015. While Pereira got to work with his own kicks and attempted to round out his game, he was quickly cornered by Wilnis and dropped with a left hook in an exchange along the ropes. This exposed an interesting quirk in Pereira’s game: while the counter left hook prevented many fighters from opening up against him, it was linked to Pereira’s feet and ability to give ground. By forcing Pereira to the ropes through the first and second rounds, Wilnis was able to commit to head-body-head combinations with his hands and land at a terrific clip without Pereira landing anything decent in return.

While Pereira lost the second fight, he looked far better than in the first and even managed to drop Wilnis with a left hook in the last round. He used his own kicks admirably against a much better kicker, but more than that—he managed his distance well. While he was “the puncher” and Wilnis was “the kicker”, Pereira stood on the end of kicking range for much of the bout, picking his shots and forcing checks and cover ups from Wilnis before committing to his punching combinations. He also made excellent use of the stepping right knee but—as Wilnis was a few inches shorter and fought with a high guard at all times—Pereira took it up the middle to the jaw instead of to the body. The knee to the head was such an issue for Wilnis that when Pereira cornered him in the third round, Wilnis picked up his left leg to obstruct the path of the knee and when the strike came it collided with his leg and turned him around into the path of the left hook that dropped him.

In the third fight, Pereira made sure to start fast. Low kicks and knees up the middle were once again the order of the day but in the opening round—as Wilnis threw a low kick, Pereira threw a high kick on the opposite side which crashed through Wilnis’ guard and dropped him for an eight count. As the two men returned to action, Pereira performed a leaping knee—pump faking his right leg and jumping into a left knee straight up between Wilnis’ arms—to score a quick knockout.

Fig. 11

The decisive nature of this third fight has caused many to forget just how much of Pereira’s game Wilnis seemed to have worked out. The biggest beneficiary of the Wilnis trilogy was Artem Vakhitov, who used the lessons learned to hand Pereira his final kickboxing loss.

Vakhitov fought a pair of bouts against Pereira in 2021, the last matches of Pereira’s kickboxing career. Vakhitov was the light heavyweight champion at the time, while Pereira was the middleweight champion, and yet Pereira towered over the Russian. The Pereira - Vakhitov bouts are curious because Vakhitov seemed to trouble Pereira more in the first, but lost the decision, and then in the rematch Pereira adapted to perform better and in turn lost a controversial decision.

The gameplan for Vakhitov was to keep a tight guard and to walk into Pereira’s chest until he hit the ropes, then unload in combinations there. It wasn’t the most nuanced way to get around Pereira’s lethal counter striking but it was enough to fluster the big Brazilian. Vakhitov even found a great application for the body jab. It was not the long, sniping shot that Pereira used but rather a ram into Pereira’s chest. Vakhitov would walk Pereira down almost entirely square and, just as both men were aware the fight was getting close to the ropes, Vakhitov would use the body jab to physically push Pereira into the ropes and step into a hitting stance, before pitching an overhand.

One unique look that Vakhitov added to the Wilnis gameplan was to use his high kicks on the counter. Pereira is so lanky that he doesn’t have to deal with high kicks most of the time anyway, but Vakhitov shot them up as Pereira rolled down behind his shoulders after big swings against Vakhitov’s guard. They were not power kicks but rather the kind of “pick up and snap” kicks you will see in karate and taekwondo. Leaning into a shin bone is always a bad thing to do in a fight though, and Pereira seemed quite rattled by these opportunistic high kicks.

In the rematch Pereira established a longer range and committed to fewer power punching combinations. Instead he relied on the right low kick as a point scorer and his jab—which he shot from a low hands position so that it came from in front of Vakhitov’s chest, right up the centre of his guard. Pereira also threw the majority of these jabs with a vertical fist so that it slipped between Vakhitov’s “earmuffs” guard more easily. The stepping right knee to the head was again Pereira’s main damage dealer, and the pump-fake knee with which he knocked out Wilnis was attempted and even scored numerous times. Ultimately Pereira was let down in the rematch by tying up with Vakhitov too often and being docked a point, and a rubber match was never signed as Pereira left for MMA.

Yousri Belgaroui and Israel Adesanya

Wilnis and Vakhitov were approaching their fights with Pereira as the shorter men, but perhaps the trickiest of Alex Pereira’s opponents was the towering Yousri Belgaroui. It was in the finals of Glory’s 2017 middleweight tournament that Pereira and Belgaroui met for the first time an in that match Belgaroui gave Pereira a kickboxing lesson.

Belgaroui stood a couple of inches taller than Pereira and fought from a higher stance, and this proved an issue for Pereira in timing and landing his counter left hooks. Where against shorter opponents he could give ground and side swipe them as they reached for him, Belgaroui was so long that Pereira could not effectively give ground without having his head snapped back with straight punches anyway. Sometimes, Belgaroui would demonstrate his speed and pitch a perfect right straight down the inside of Pereira’s left hook as in Figure 12. The right straight down the inside of a left hook was considered by Barney Ross to be “boxing’s most lethal counterpunch.”

Fig. 12

On other occasions, Belgaroui would get it wrong or Pereira would seemingly time his left hook correctly, but the punch would hit Belgaroui’s shoulder or catch him high on the head. Then, as his opponent should have been collapsing into a puddle on the floor, Pereira would get poked twice by the barge poles hanging from Belgaroui’s shoulders. This was where Belgaroui put Pereira through the ringer: he drove a frenetic pace. Pereira thoughtfully set his traps and threw his all into his blows but whether he hit or missed, if Belgaroui found that he was still conscious he threw two or three more punches while Pereira was recovering. When Pereira tried to clinch and hold, Belgaroui roughed him up there too.

Fig. 13

Variety also made Belgaroui more difficult to read. He would skewer Pereira with a jab that was too long to effectively counter with the left hook, but he would also lead with knee strikes, front kicks to the body, and low kicks. Figure 14 shows a typical combination from Belgaroui, opening with a very conservative inside low kick to effect Pereira’s balance, jabbing in off it, and landing a powerful right low kick on the end. These are not killing strikes but are annoying and exhausting for a man waiting on his perfect counter.

Fig. 14

The second and third Belgaroui fights show the best of Alex Pereira as a ferocious competitor and an opportunist. While Pereira kept trying, his left hook never proved to be much of a hassle for Belgaroui through their three fights. What Pereira was able to use was Belgaroui’s fearlessness. Where many opponents cowered and covered up when Pereira walked them to the ropes, Belgaroui ricocheted from one side of the ring to the other, throwing punching and kicking flurries as he came off the ropes. It was in these moments of Belgaroui biting down on his mouthpiece and fighting his way out of trouble that Pereira finally found him. In the second fight it was one good right hand, timed as Belgaroui tried to throw a low kick off the ropes. In the third fight it was one good right hand just as Belgaroui opened up with a one-two. They were not clean, clinical masterclasses and all the traits that Belgaroui owned that annoyed Pereira still existed, Pereira just forced his way into the fight and found his mark in spite of all of that.

Many aspects of the Belgaroui fights tie in with issues Pereira faced in his earlier fights with Israel Adesanya. Neither Belgaroui nor Adesanya were at a significant reach or height disadvantage against Pereira and this seemed to throw off much of his counter left hooking. Switch hitting was also a good portion of both Belgaroui and Adesanya’s games. Belgaroui tended to do it in wilder flurries, while Adesanya’s switch hitting was closely connected to Pereira’s own countering off kicks.

Where Pereira threw the right kick to retreat into his left hook, Adesanya threw a step up left kick from orthodox stance in order to drop the leg down behind him and retreat into a southpaw position. From this southpaw stance it was an intercepting knee against an aggressive opponent, or a left front kick or high kick, or a left straight. This simple stance switch triple attack gave Pereira enormous trouble across both fights.

Pereira also struggled, once again, with an equally rangey man who could jab. And where Pereira liked to roll down behind his shoulders after big punches, Adsesanya would extend his arm out as a frame to make it difficult to return on him. This look in particular, combined with good ring generalship and feinting, seemed to give Pereira a lot of trouble. But the style of Adesanya and how Pereira was able to overcome it are perhaps better suited to a study of Israel Adesanya himself.

Alex Pereira’s feats in the kickboxing ring can be ranked among the greats of that sport. He introduced weapons that ran contrary to the traditional best practices of kickboxing—a pivoting left hook, a bladed body jab—and succeeded because of them, not in spite of them. He is a reminder that inspiration can be found in any combat sport and, with diligent work and understanding of context, can be brought to bear fruit in another.

—————————————————————————————————

Check out the previous entries in the Advanced Striking 2.0 series:

Dustin Poirier

Tommy Loughran

Anderson Silva

Badr Hari

Jose Napoles

Mauricio ‘Shogun’ Rua

Igor Vovchanchyn

Jose Aldo

Saul ‘Canelo’ Alvarez

Alexander Volkanovski