Killing the King: Jon Jones Revisited

The Killing the King series is one I have written in spurts from Bloody Elbow and Bleacher Report to Fightland and Vice Sports but it has been a few years since our last deep dive into champion film study. The point of this series is to dig into the performances and training of the absolute best fighters in the world and look for exploitable habits. The choice to not use the word “flaws” there was very deliberate. Looking for flaws in UFC champions is often a thankless task, habits are where the money can be made. There aren’t too many doofuses out there tripping over their own feet or throwing their chin up in the air every time they punch but winning UFC titles in spite of it. Yet for all the talk of being formless and shapeless like water, the fighter without habits does not yet exist.

One of the reasons for the lengthy hiatus was a lack of long-reigning champions. The majority of the UFC’s titles were bouncing all over the place in the last few years. The pillar of stability throughout this time has been Jon Jones—as reliable in the cage as he is disaster prone outside of it. He has been the champ, not the champ, and the sort-of-champ in that time, but he has never lost and it has not even looked close. We have already looked at Jones twice in this series—way back at Bloody Elbow and then again at Fightland but rather selfishly, Jon keeps getting better. However, the trick with focusing on habits instead of hoping for a magic weakness is that when a fighter adds new elements of his game he is also adding new habits and opportunities.

Because of the existing material we have produced on Jones, I want to take this opportunity to consider him specifically in the light of his only two rematches. In his four bouts with Daniel Cormier and Alexander Gustafsson we saw Jones genuinely tested through very different tactics and fighter types. While those will be the focus of today’s analysis, it is probably worth beginning with a recap of Jones’ usual style.

The Staples

One of the main tenets of Killing the King has been that if you don’t know where to start, work on taking away the fighter’s A game. Think about how much less effective Georges St. Pierre was when Johnny Hendricks checked his lead hand and prevented him from jabbing all night, or how much Anderson Silva disliked having to lead, or how uncomfortable Ronda Rousey was the moment an opponent started circling away from her straight line charges. Take away a fighter’s absolute favourite thing to do and you make him fight a less practised, less comfortable game. That is a solid foundation from which to start.

When Jon Jones burst onto the UFC scene he was a blur of spinning techniques, fancy trips, and punishing ground and pound. He won the UFC title while still mostly throwing anything he wanted out there and seeing what stuck. Once he held the UFC light heavyweight strap though, Jones quickly matured into a more methodical, tactical fighter and took on many of the looks we associate him with today. The difference between what we might call “Rising Superstar Jon” and “Championship Jones” was that the former seemed largely concerned with seeing what he could get away with in the course of winning, while the latter builds his performances around never even allowing his opponent into the fight. Even now, after a decade of dominance and with his hairline retreating to the back side of his head at a rate of knots, Jones relies on the same few staples to undo opponents of markedly different builds, styles and abilities.

At his core Jones is an attrition fighter who sets himself up to keep fighting for the full five rounds, then drives up the pace when he sees his opponent is flagging. For the most part he does this with his distance kicking game.

Jones always relied on his kicks, and particularly his low round kicks, but Jones’ fights against Quinton ‘Rampage’ Jackson and Vitor Belfort introduced much of the MMA world to the low line side kick and oblique kick. These two linear strikes to the front of the knee or thigh were treated with disgust by Jackson and Belfort—Jackson even believed the technique to be illegal—and fight fans quickly came to the conclusion that it was both dirty and sport-breakingly unanswerable.

Jones’ kicking doesn’t work in isolation though, it is his management of distance that makes all the difference. Whether it is cautiously drifting around the cage or breaking into a sprint to get away from the fence, Jones knows where he needs to be at all times and even if his hands are the least impressive facet of his game, Jones demonstrates mastery of all the elements of the sweet science of boxing that aren’t just throwing hands.

For the most part the low line side kick and the low line oblique kick (or chasse bas for the Francophiles) is a jamming weapon. That is why it made such easy work of Belfort and Jackson. Jackson’s plan was always going to be to plod into punching range and start swinging. Belfort’s style is largely based around blitzing in on a straight line. Neither can do that without putting their lead leg into range first and then, as Bruce Lee said in that one episode of Longstreet—longest weapon, nearest target.

No tactic is unstoppable though and there are now a number of ways to defuse the straight kicking on show in MMA. We covered this extensively in Stomping the Knee: A Guide to Countering MMA’s Most Ungentlemanly Tactic. One of the smarter ones was T.J. Dillashaw’s stance switch before entering. After Assuncao started jamming him with low line side kicks Dillashaw got in the habit of showing one leg as the leg to be jammed and quickly switching before he entered with strikes. Dillashaw also did well faking an entry and then physically reaching down to parry and slide down the side of the low line side kick.

Thinking outside the box, Robert Whittaker surprised many of us by answering Yoel Romero’s side kicks with leaping, rear footed front kicks. In the course of that fight Whittaker threw more front kicks than almost all his other strikes combined and it looked bizarre, though it proved to be an in-the-moment adjustment to Romero injuring Whittaker’s knee on the very first kick. The thinking has always been that taking a straight kick in the standing leg while kicking could be disastrous, but by throwing himself bodily into the front kick from then on, Whittaker was able to drive Romero’s weight back any time the two came together—paradoxically protecting his standing leg by leaping into Romero on one foot.

The truth of the low line kicking game is that the opponent’s kick—whether it is a step on the knee or a wholehearted stomp—is only effective within a very small space in the cage. They need to find your lead leg and if your lead leg is a little less predictable, they run the risk of getting on one leg and locking themselves on the spot for nothing. But we’ll get onto the men who defused these kicks against Jones himself in a minute.

The other area where Jones really excels is in the clinch. Jones is one of the most creative and smothering clinch fighters in MMA history. He basically invented the spinning elbow in an MMA context. Guys occasionally tried to time it as a counter out in the open, as is the most common application in Muay Thai, but it was Jones who realized that by posting his head and freeing his hands with the opponents back to the fence, he could spin for elbows with a static target and no repercussions. You will see everyone from Alexander Volkanovski to Rafael Lovato attempting this move nowadays.

That head post is incredibly important because it allows Jones to stand his opponent bolt upright while he can move his hips back and create power on both punches and knees with his whole body. While Jones’ hands look sloppy and wide on the outside, his infighting has been magnificent.

Notice that by posting his head on his opponent Jones can drive them into the fence and flatten them out, while maintaining a stance from which he can hit with power.

Again, posting his head beneath his opponent’s he digs body shots like a boxer from the 1940s, but turns over elbows to the head as well—then folds down behind them to defend himself from returns.

It is absolutely beautiful stuff and it shocked many that he was so comfortable doing it against the powerful slugger, Glover Teixeira. But that’s the beauty of it, by driving the opponent into the fence and posting his head he has pushed them up out of their stance, removing much of their power. And that is the point of the classical infighting “inside position”: there aren’t many men who can hit hard directly in front of their own head and chest—where the infighter’s head is posted.

A very exaggerated classical inside position from Edwin Haislet’s ‘Boxing’. The head post serves the same purpose though, obviously, this is asking to be snapped down into a front headlock.

Not only does the head post allow Jones to free his hands and do some decent hitting while pushing his opponent into the fence, it also gives him the chance to stretch the opponent’s underhook. If the elbow clears his body line he can quickly snap on his favourite arm crank / shoulder lock. Another technique that was thought to be movie bullshit before Jones started slapping it on everyone he fights.

Once Jones had tasted Daniel Cormier’s bus driver uppercut in the early rounds of their first fight, he committed to shutting Cormier’s right hand down in the clinches. This is where Jones’ ability to lean on opponents is quite wonderful. Not leaning in the way that “Andrei Arlovski going to a decision” sense, but being able to get his hips away from his opponent and put his weight on them even when using overhooks to control them. Taking an overhook against Cormier, Jones would use both hands to control Cormier’s right wrist around this overhook, but was still able to post his head and create space to land good elbows on Cormier’s right side off this control.

Jones has an overhook with his right arm, but is controlling Cormier’s right wrist with both hands (1). Notice that his hips are still back. Momentarily releasing Cormier’s right hand he is able to land a good left elbow on Cormier’s undefended right side (2) before dropping back into the clinch.

When Jones isn’t posting his head to create distance to strike effectively in the clinch, he will go to a shoulder butt to his opponent’s face. Sometimes he will even jump when doing this, like Fireman Jim Flynn headbutting Jack Johnson. Partly this is Jon Jones doing his “I’m inventing a move right now” thing, but also it can create space for him to post his head afterwards.

Jones leaves the floor to slam his shoulder into Anthony Smith.

That’s the Jon Jones set list. You can rely on him to play those hits when he gets in the cage and while there is more to him, when he goes past these it is pretty much his own choice. Most of the opponents he meets cannot cope with him at range or in the clinch. Yet two of Jones’ opponents did an excellent job of complicating his A game. You didn’t miss some kind of Anderson Silva type implosion, he still won, and that brings us onto our focus today: Jones’ toughest opponents and his adaptations in the only two rematches on his record.

Alexander Gustafsson

Gustafsson’s chances weren’t highly rated coming into the first fight, and you might subscribe to the idea of Jones partying his camp away and not taking Gustafsson seriously. None of that actually matters to the specific ways that Gustafsson troubled Jones. Gustafsson’s performance was built around lateral movement and being difficult to read. Watch through the first round of Gustafsson vs Jones 1 and you will see almost no effective low line straight kicks because Gustafsson is so laterally mobile. Kicking the lead leg is easy when you know it is stepping in straight in front of you, it is much more difficult when you’re busy trying to follow someone who is skipping sideways around the cage with their feet almost level.

Not only did Jones throw his low line kicks less frequently, he often mistimed them because of Gustafsson’s constant movement and feinting. Many times this meant that he would step on Gustafsson’s thigh but be unable to extend into the kick and Gustafsson would push right through into his boxing. To see an extreme example of this in action check out Oliver Enkamp’s loss to Danny Roberts in the UFC.

As we have already said, low line kicks aren’t a straight line of unstoppable power extending from the fighter’s hip, they have a small area of actual effectiveness and if you connect too close or too far away the kick isn’t going to have the desired jarring / jamming effect.

Mistiming a low line kick actually saw Jones suffer the first takedown of his career. If a man who can comfortably prevent Daniel Cormier from taking him down through two fights is being taken down by a Swedish boxer with no wrestling credentials, you know that getting out of position on a kick really makes a difference.

Gustafsson also ruthlessly exploited Jones’ tendency to reach for his opponent and to try to frame off their face. Gustafsson was able to build the body jab into beautiful low-high combinations as Jones got into the bad habit of simply trying to stiff arm his man away.

Jones’ adaptations in the rematch were remarkable because he made Gustafsson look completely unthreatening, while still displaying all the loopy punches and awkward reaches that he showed in the first fight. The difference was that this time, Jones didn’t take the centre of the cage and he forced Gustafsson to pursue him. And where Jones had his successes in the first fight out of orthodox stance (spinning for a back elbow against a slipping Gustafsson, throwing a switch high kick at the same opening), he fought the rematch almost entirely southpaw. As a southpaw, Jones was able to check Gustafsson’s lead hand and deny the jab. Each time Gustafsson tried to advance and slide down the outside of Jones’ lead foot to line up the right straight, Jones simply retreated and circled out to his left.

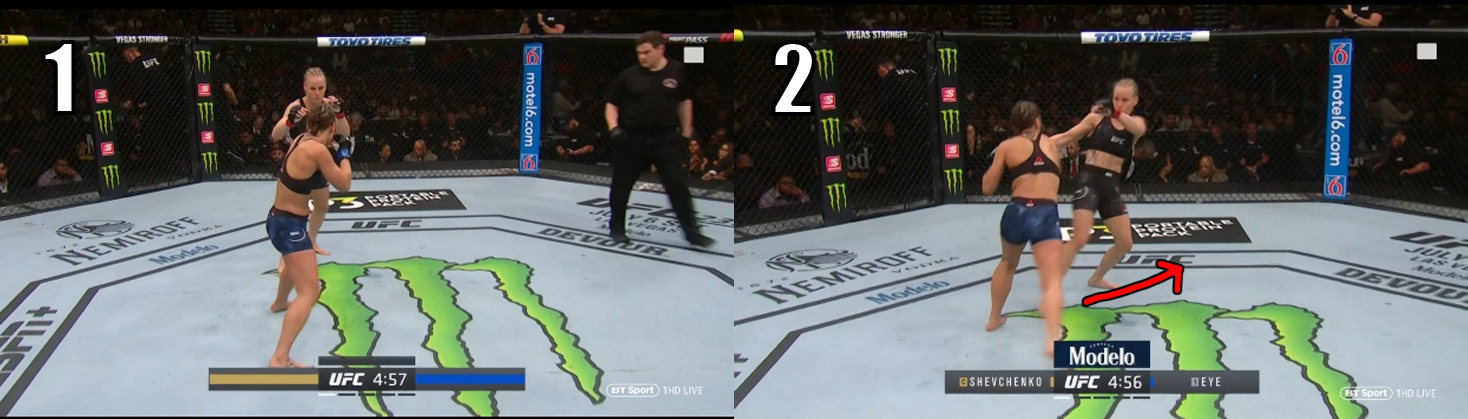

This spiralling out—retreating and breaking the line of attack at the same time—is a constant in Henry Cejudo’s recent fights against southpaws, but was also on show in the Valentina Shevchenko vs Jessica Eye massacre. Each time Eye moved to close the distance, Shevchenko broke the line of attack and turned her.

As Eye advances, Shevchenko gives ground and circles towards her own left. As Eye turns to face her she can score body kicks into the open side, where only Eye’s forearm protects her.

After every turn, a gut munching kick came up to wind Eye or pin her right elbow to her side. This circle-and-kick was much of Jones’ performance in his second fight against Gustafsson, and it hampered Gustafsson’s ability to throw his right hand comfortably.

There were even instances where Gustafsson switched stances on Jones and Jones would switch stances just to maintain that open guard match up and circle out.

The beauty of Jones’ performance was that Gustafsson could not cut angles on him and follow him at the same time. In their first meeting Gustafsson was floating around Jones, who slowly pursued from the centre of the cage. Jones had to put a lead on Gustafsson and try to time him circling with back kicks. In the rematch, Jones forced Gustafsson to be the pursuer instead and, in doing so, could predict where Gustafsson would be far more accurately. Reviewing that fight you will notice that while Jones deliberately didn’t lean as heavily on his famous low line straight kicks, he was able to connect them successfully after drawing Gustafsson into following him.

Jones circles off the fence (1) and back towards the centre of the cage (2). As Gustafsson moves across to follow Jones, his path becomes predictable and Jones scores a good oblique kick to the lead leg.

Also worth noting was Jones’ constant threat of a takedown as Gustafsson moved towards him. By ducking in on Gutafsson’s hips just as Gustafsson was stepping in, Jones could both put the fear of a reactive takedown into the Swede, and smother any combination work. Furthermore, because Gustafsson would dig underhooks in answer to Jones’ clinch attempts, Jones was able to surprise Gustafsson with his americana style arm crank twice in the early going of the fight, a great thing to be able to do against a fighter whose quick right hand is a selling point.

As Gustafsson pursues Jones across the ring, Jones ducks in on a takedown attempt, though he throws his left arm out wide (1), seemingly unconcerned with Gustafsson getting the underhook. Jones half heartedly chases the leg while Gustafsson digs in his underhook (2).

As Jones come up into a standing clinch he posts his forehead on Gustafsson’s shoulder (3) and catches his favourite arm crank (4). Jones executes this technique in most of his recent fights, often off this set up, and always on his opponent’s right arm.

Daniel Cormier

Going into their first fight, most fans were fascinated by the match up Daniel Cormier posed for Jon Jones primarily because of the possibility that we could see Jones forced to work from his back. As if turned out, Jones was able to stop Cormier from getting the takedown through the bout, but Cormier’s clinch work gave Jones significant difficulties.

The rematch between Jones and Cormier provided some of the finest mixed martial arts we have ever seen. No longer was Cormier a wrestler with heavy hands, looking for the cartoonish, wound-up uppercut. Instead he was now a serviceable and awkward striker.

Cormier’s recent career has been built around use of a George Foreman / Sandy Saddler style ‘Mummy guard”. That is to say he reaches to check both of his opponent’s hands, his arms extended in a style reminiscent of a Scooby Doo style ancient Egyptian mummy. By doing this Cormier can smother his opponent’s offensive options and draw them into a pure handfight before sneaking in his own offence, as seen here against Volkan Oezdemir. Controlling a fighter’s hands also means that you can dictate when he gets the chance to throw—take away control, he’ll throw, and you have your chance to enter on a takedown. By changing the contest into a handfight, Cormier was able to outjab Stipe Miocic, a man who uses one of the most educated jabs the heavyweight division has ever seen.

Jones uses a great deal of double hand checking himself. This meant that the second Jones – Cormier fight took on that strange dynamic that Lyoto Machida vs Chris Weidman and Robbie Lawler vs Johnny Hendricks II did. Both men stood in striking range, checking their opponent’s offensive options and then tried to trick him with a crafty straight around the side or up the middle. However when Jones turned his usual elbows over, DC was repeatedly able to fold down behind his own shoulder and elbow or duck the elbow outright.

Cormier meets Jones in a handfight, both men are extended and blocking the other’s straight blows, but are undefended around the side (1). However if you do this regularly, you know the opening for a swing around the side is there and DC ducks under Jones’ usual folding elbow (2).

Cormier’s success in the second fight came largely in the same way that Jorge Masvidal had success against Donald Cerrone—he repeatedly closed the distance and tried to wedge his way down the centre, countering off Jones’ kicks. Cormier didn’t perform slick catches and parries on Jones’ kicks above the waist as Masvidal did, but when Jones performed low kicks, Cormier found good counters. Reiterating that point that the low line straight kicks only have a small area of effectiveness even within their own path, Cormier was able to withdraw his lead leg into his stance and then come back with counters as Jones was left out of position.

Cormier withdraws his lead leg from a Jones side kick (1, 2), Jones is left out of position and Cormier counters with a good right low kick (3).

Cormier withdraws his lead leg from another low line kick (1, 2), before stepping back in with a good right hand (3).

You will notice that Cormier was actually reaching down for parry those low line kicks, and you will think back to the head kick the Jones scored to win the fight. However, this particular action is not really connected with that—in fact most of the time that Cormier parried the low line straight kicks it was because he was in range to do so and kept his other hand high to protect against a Stephen Thompson style side kick to high round kick switch up. The head kick landed because Cormier was overreacting with both hands when he suspected a body kick was coming—a response to Jones’ very effective body work throughout the fight.

Cormier actually did very well with counter low kicks. This drove home a point about Jones and low kicks generally. The thinking has always been that Jones could be vulnerable to low kicks. Part of that is because of his “skinny chicken legs”, and part of that is because even Quinton Jackson had success kicking Jones’ legs. The fear, of course, is kicking Jones in the thigh and immediately being taken down as Mauricio ‘Shogun’ Rua was.

What you will notice about Jones’ style, however, is that he’s hardly Lumpinee Khalil Rountree. That is to say he’s not repping traditional Muay Thai in MMA—his stance is normally more of a traditional martial arts or boxing stance. He’s not square and waiting to check or counter kicks because his main defence is his movement and distance management. This means that Jones’ feet are often out of position to check or step in on low kicks. You will have noticed too that Jones’ answer to getting out of position is to sprint his way out to distance—this is what gets him accused of running by Jackson and others. But this reliance on movement means that he is even more susceptible to being low kicked after throwing himself out of position with his own kicks and likely to suffer significantly over the rounds if his footwork can be slowed a little by attrition.

Regardless of whether you are counter kicking or swinging for his head, between the first Gustafsson fight and the second Cormier fight it is apparent that one of the keys to getting in on Jones on your own terms is to draw out the kicks and get in through the wake.

Jones’ hands aren’t really anything to write home about. The southpaw left hand to the body that he used against DC, Gustafsson and Smith is a great weapon for him though. This is usually paired with a nice fake single leg to straight left down the pipe—one you will remember from Alexander Shlemenko versus Gegard Mousasi last year.

Tap the knee, punch the face. It’s a classic.

But the majority of Jones’ work with his hands is defensive and he can often be drawn into reaching for his man. Both Cormier and Gustafsson had success hooking off the jab, and drawing his rear hand forward before swinging around behind it. Similar to Curtis Millender, he is somewhat protected from the downsides of this by his height and range where a shorter fighter would be clubbed with clean hooks much more often for the same habit. But that’s the game—you don’t fight for the build you don’t have and there’s no shame with getting away with something entirely because you’re tall / long / fast / powerful.

It feels like a cliché to write about how well rounded a fighter is, but Jones’ two best areas—the extreme outside game and the clinch—cover a lot of bases. If you want to box him and you can get inside the long game, he’s going to clinch you. If you want to wrestle him, he’s going to keep you on the end of his kicks. Exploiting his habits is going to rely on a great degree of skill, but also on a different gameplan depending on the man applying it. For instance, Daniel Cormier looked great in the second and third rounds of the rematch—up to the head kick, of course—because he could go forward and put pressure on Jones in the striking, and when Jones ducked in to tie up, Cormier was able to handle him. In fact, Jones was so out of position on some of his duck ins that Cormier was able to hit nice foot trips and threaten Jones’ neck—a Jones favourite!

This was notable not only because Cormier was scoring decently and stifling a lot of Jones’ work, but because by staying in Jones’ face he was making Jones work. Jones’ conditioning is always top notch, but he protects his gas tank with well controlled distance striking and a smothering clinch. Two more rounds of Cormier – Jones II would have been a very interesting insight into Jones’ conditioning under duress.

But of course, coming forward and trying to strike Jones didn’t work a jot for Gustafsson in the second fight. Even though he could stuff the takedowns decently it was an all consuming effort and he couldn’t get any combinations going for most of the fight. The moment he got a little bit more adventurous, Jones ducked in to meet him and got the takedown that led to the end of the fight. Gustafsson’s strength is in picking and moving, particularly in combination, and it’s far easier to do that when the other man is walking onto it.

Final Thoughts

It might be a bit pessimistic to poo-poo Thiago Santos’ chances but from everything we have looked at, he doesn’t seem to be the man to pull it off. His kicking game is not so much a game as it is standing well out of range and then running into kicks. He doesn’t really counter fight so much as counter swing. He’s not going to jab in on Jones and provide pressure to get him reaching and then clock him around the side. He’s unlikely to meet Jones in the handfight with success. He’s probably not going to be able to handle Jones in the clinch more than to stall Jones out and waste his own energy in the first couple of rounds.

No, to beat Jon Jones quality striking, competent clinch work and most importantly the ability to control the distance and location of the fight will be key—whether that be outfighting and keeping him in pursuit, or pressuring him towards the fence to get him reaching and taxing his gas tank with a high pace. But then you look around the light heavyweight division and it all just seems so bleak. All Jones’ rivals are gone and all that seems left to trouble him is father time and the promise of Dominick Reyes or Johnny Walker’s potential off in the distance.

If you fancy reading some more stuff like this, check out my Jones vs Santos Preview and my Nunes vs Holm Preview at Unibet.

![Usyk's Place in the Heavyweight Division [Unibet]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5999f691be42d6f75fa626d6/1561664622828-WPA2VEGG3TAARPV2DI1Q/Usyk+Header.png)