Combat Jiu Jitsu and the State of Grappling in MMA

While it was a bit gimmicky to begin with and earned this writer’s ire by replacing the beloved Eddie Bravo Invitational format, Combat Jiu Jitsu serves a useful purpose to the grappling or MMA student. Very few of the world’s best grapplers are going to get to a world class standard in MMA simply because of all the other elements involved, but Combat Jiu Jitsu gives us a window into how the ever changing no-gi grappling “meta game” holds up to a swift smack in the face. This is important at a time when every failed leg lock in MMA sees that entire sub-discipline of grappling labelled as ineffective, only for Charles Oliveira to fight the next weekend and use them to sweep his opponent successfully.

Scrambled Legs

The leg game took a brutal loss in the very first match of last weekend’s Combat Jiu Jitsu lightweight tournament. The B Team’s Damien Anderson stood over Adrian Madrid in a leg entanglement and smote Madrid with a downward palm strike. It was almost identical to Grant Dawson’s knockout of Leonardo Santos in the UFC back in March 2021.

And it brings us back to what makes Charles Oliveira’s leg entanglement game so strong: he isn’t necessarily bothered about finishing a heel hook as much as he is about using knee reaps and calf slicers to turn his opponent’s knee away from him so that they cannot effectively strike down on him. Everything that Oliveira does from the bottom seems to be focused on creating movement, he is seldom just laying on his back in range of the opponent’s hands. Of course life is made a little easier for Charles with the legality of upkicks in proper MMA, a move which is strictly prohibited in Combat Jiu Jitsu.

Yet leg entanglements remained a constant feature through the tournament. Even if bottom position threatened the prospect of getting struck in the head, many of the competitors were willing to sacrifice top position to hunt a submission. Both Damien Anderson and Jordan Holy looked to go back towards the legs and attack heel hooks after already passing guard. Holy got the submission in his opening bout by exposing the heel as his opponent looked to replace guard, and only then throwing his own legs into position.

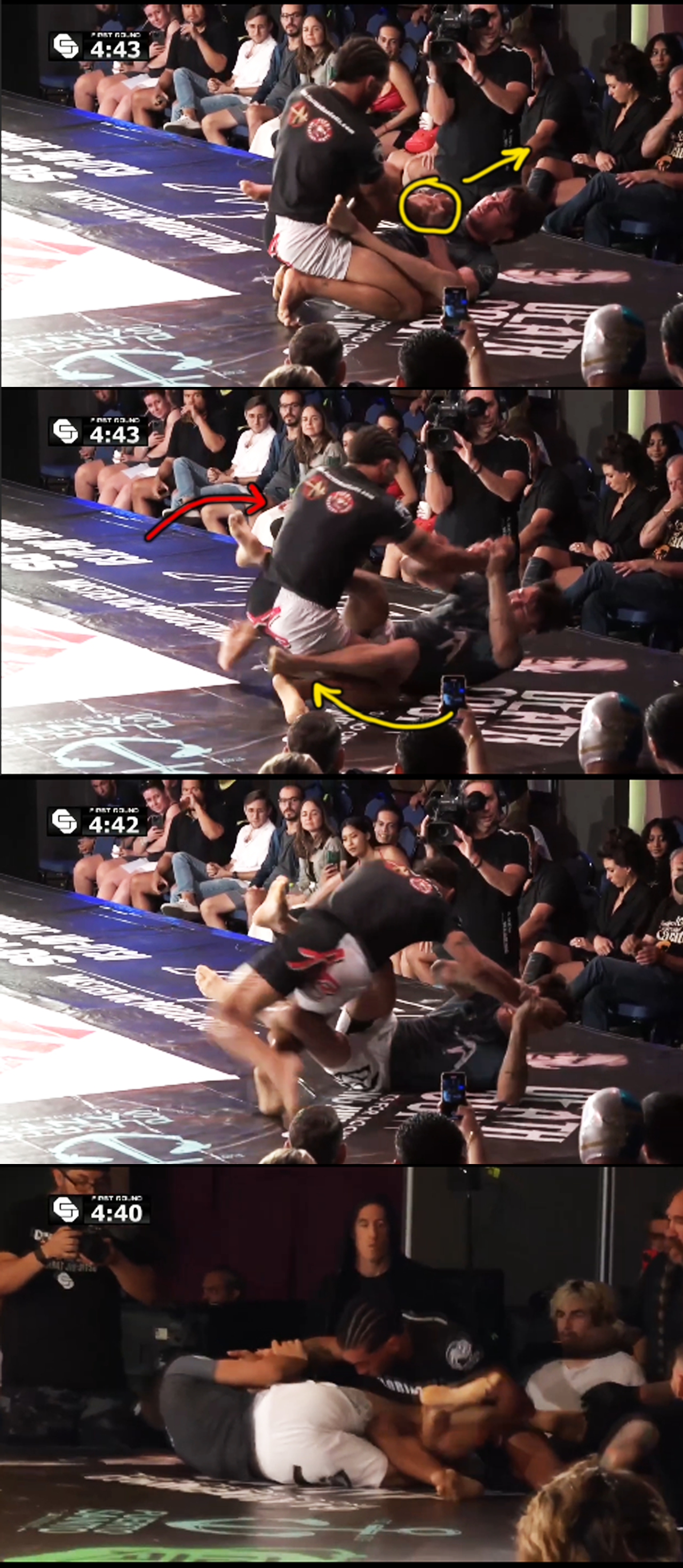

Perhaps the most compelling piece of evidence against the leg lock game was Ethan Crelinsten’s performance against Kieran Kichuk. Crelinsten had some scrambly matches in his no-gi career wherein he navigated the threat of his opponent’s leg attacks in order to expose their back and secure back control. In this bout, however, he used his leg lock experience to effectively counter-punch from within leg entanglements. Working from the 50-50, Crelinsten would wait for Kichuk to try and roll over the leg into backside 50-50 or tilt him outward, and give him a swat. In the instant that he landed the palm strike, he would get his knee to the floor and hide his foot again.

Seven or eight good strikes as Kichuk tried to expose the heel had Kichuk cut open and looking worse for wear before Crelinsten got on top, took the back and secured his rear naked choke.

The curious part about the palm strikes is that in many matches they made the difference, and yet in others they were a complete non-factor. This competition is still a step removed from prize-fighting as half the competitors are friendly with each other, and the semi-finals saw match ups between the two 10th Planet representatives and the two B Team representatives. The B Team competitors refused to strike each other, while the 10th Planet match was decided when Nathan Orchard began striking halfway through the match and clearly rattled the CJJ featherweight champion, Keith Krikorian.

Another reminder that this isn’t a direct replication of the ground fighting of MMA was Diego Lopes’s work from the bottom against UFC vet, Jim Alers. Alers took top position and started trying to maul Lopes as you would expect, but Lopes found he could upset Alers as much from the bottom with wound up slaps of his own. Alers would try to bury his head, and Lopes would threaten an omaplata, or Alers would kneel back upright, and Lopes would put his feet on the hips and start looking for awkward scissor sweeps.

A nice two-on-one grip into a scissor sweep. It took a while to untangle the legs but Lopes did get on top off this.

It was intriguing to watch Lopes grapple from a sort of leg-press position—and BJ Penn used to play a lot of guard with both feet on the hips in MMA, attempting to create space for stand ups—but it seemed as though Alers’ decision to focus on the grappling more than the striking about halfway through the match manufactured these unlikely-in-MMA positions.

Hand Trapping on the Mat

Often the influence of grappling on MMA is considered one-way, as MMA fighters try to apply the techniques of elite grapplers in their own sport. In truth MMA influences pure grappling just as much or more. For instance, Marcelo Garcia made the north-south choke famous in grappling, after seeing Tito Ortiz try it at ADCC 2000. Using the legs to trap the opponent’s hands from back mount is now a huge part of no-gi grappling, but the first guy making waves with it was BJ Penn from his very first MMA fight. Hell, the 50% of high-level no-gi that isn’t leg locks is now mainly wrestling up, standing out of the turtle, and mat returns—techniques readily adapted from the existing grappling trends of MMA.

Most recently, Khabib Nurmagomedov’s wrist trap or “Dagestani handcuff” has become a nuisance on the grappling scene as well, with competitors catching the far wrist as an opponent sits up to scoot their hips back and reclaim guard. Gordon Ryan famously used this against Yuri Simoes in their second match. At CJJW 2022, Kieran Kichuk demonstrated the power of this grip again in a beautiful sequence against Mikey Gonzalez. It began with Kichuk coming up from the bottom of butterfly guard with double underhooks, just as Jack Shore did in his most recent UFC fight. This a pretty old school technique, but it asks the question: “why would I attempt a fancy butterfly sweep when I could stand up into a free bodylock?”

The sweep brought Kichuk down into Gonzalez’s half guard and he was able to press Gonzalez flat. The half guard is the watershed in the positional hierarchy of jiu jitsu where, for the bottom man, things go from “an even fight” to “getting smashed.” If he has a knee shield or a butterfly hook it is more of a guard, but if he is flat to his back with no knee shield or butterfly hook, it is a pin where he is clinging to one leg. Gonzalez made a decision to clear Kichuck’s head with his top arm and sit up onto his elbow, perhaps looking to attach to a kimura. Whatever his intention, Kichuk immediately shot both hands to Gonzalez’s posting arm and folded him down on top of it.

The potency of this hand trap in MMA comes from the fact that the opponent now only has one hand to defend punches. The attacker only has one hand free himself, but the Dagestani handcuff is effectively a cross hand trap. In this instance, Kichuk’s left hand is controlling Gonzalez’s left hand. Both standing and on the ground, Gonzalez’s left hand performs the task of shielding him from swings to the left side of his head, which would come from Kichuk’s right hand—the one that is free. Gonzalez is left in an awkward position where he can stay on his side as Kichuk palm strikes over and under his free arm, or turn to his knees and expose his back.

Gonzalez went to his knees after a few good whallops and Kichuk took his back, finishing with a rear naked choke a minute later.

On the subject of hand trapping, in the same week that Rickson Gracie popped out of the woodwork to announce that he has added another 50 wins to his record, Ethan Crelinsten made great use of Rickson’s signature gift wrap position. This is achieved by catching the opponent’s wrist from behind their head.

The gift wrap has come back into vogue in jiu jitsu since athletes began copying Gordon Ryan’s cross hand grips from mount: forcing one wrist to the floor and encouraging the opponent to turn towards it and present the gift wrap. Against Nathan Orchard, Crelinsten was able to first use the gift wrap to land some decent strikes, and then later threaten the gift wrap before letting it go to posture up and sneak in some even better strikes on the shelled up Orchard.

Three Quarter Mount

While it was hardly a secret, the weekend’s Combat Jiu Jitsu also demonstrated the value of the three-quarter mount. This is the position where a fighter is almost entirely in mount, but the bottom man has caught an ankle with his legs.

In pure grappling three-quarter mount is a job half done: the top man has to get a good cross face or underhook in order to straighten his opponent out, pummel in the other foot in, and free his leg to achieve full mount. On the other side of that, a quick knee-elbow escape from the bottom man and he is back to half guard. This is because assuming the three-quarter mount is essentially jumping in at the mid-point of the classical knee-to-elbow mount escape, demonstrated below by the GOAT instructor, Lachlan Giles.

In MMA, three-quarter mount is mount. The punches from three-quarter mount are the same as those from mount, except the bottom man is stuck on one side and cannot bridge or throw his legs up to break the top man’s balance as he lines up his punches. Footage from Demian Maia’s UFC fights against Gunnar Nelson and Neil Magny contains a dozen instances of Maia advancing from half guard to three-quarter mount and the opponent either turtling or conceding full mount because they have to worry about the punches, even from the friendliest, least committed ground and pounder in MMA.

A great example of this in Combat Jiu jitsu was Damien Anderson’s match against David Weintraub. Anderson entered a knee cut, before sneaking it across into a three-quarter mount. In a jiu jitsu match he would still have work to do here and Weintraub would have a great chance of re-guarding. Weintraub started trying to force Anderson’s knee back into his guard, but with his hands down by his hips and Anderson loading up palm strikes he quickly reconsidered and opted to turtle instead. Anderson took the back and finished with a rear naked choke moments later.

The Crelinsten Game

The man who won the Combat Jiu Jitsu Lightweight Worlds last weekend was perhaps not coincidentally the man who best adapted to the rules. Ethan Crelinsten is a former Danaher Death Squad member and now part of the B Team. He has great leg attacks, great back attacks and, to the surprise of everyone watching, maintains a strong pimp hand.

The highlight of this tournament was Crelinsten’s work from the back and mount. In each match that he achieved back control, he still prioritized being on top. This is something that even top level MMA fighters will stray from and end up paying for it. A lot of the time a great MMA grappler will achieve backpack position and happily fall to his own back, so that both he and his opponent are looking up at the ring lights.

This is a problem for several reasons: the first is that everyone in MMA is good at spinning back into closed guard from back control. Think of Anthony Pettis who has made such a specialty of this that he’d often rather give up his back with hooks and escape from there than be stuck underneath a pin. The second is that the fighter “controlling” the position is made to carry his opponent’s weight instead of vice versa. And the third is that the fighter in back mount cannot effectively strike. This means that when his opponent can defend the rear naked choke—made a lot easier by both men wearing padded gloves—the fighter on the back has no other offence spare giving up the back and attacking some kind of armbar. Think of Aljamain Sterling vs Petr Yan or last weekend’s Damon Jackson vs Daniel Argueta where one man was clearly in control, but to little real effect.

Crelinsten was able to imitate a tactic that Shinya Aoki and Rafael Lovato Jr. used successfully in MMA. After acquiring a body triangle from the back, he allowed his free foot to go inside of the opponent’s opposite thigh and, combined with an elbow prop, used it to turn into top position. Below is an example of Lovato doing this in the fight where he dethroned regional great, Gegard Mousasi.

Crelinsten was able to do this a couple of times in the final of the Combat Jiu Jitsu Worlds, against Nathan Orchard. From back position, whenever Orchard rolled so that they were both belly up, Crelinsten threatened to strangle him, locked his legs in a body triangle, and then got up to an elbow and turned into top position.

This mounting body triangle offers the benefits of mount in terms of striking with gravity, while locking the top man closer to the back than the mount. It doesn’t have a whole lot of use in pure grappling but when you see it executed in fights with striking it tends to only be momentary because it’s a seriously bad spot to be in for the bottom man.

Notice that the position is effectively the three quarter mount discussed earlier, with Orchard forced onto one side. But this time Crelinsten’s right knee is backstopped by hisleft foot and the strength of the body triangle with both men’s weight on top of it. There is no real threat of a knee-elbow escape, so the choice for the bottom man is stay there and get hit with right hands, or turtle.

There is plenty more to be said about Crelinsten’s work from the back but the man himself released an instructional on it at BJJ Fanatics that is well worth any grappler’s time. One of the themes that you could see in this tournament though was a focus on the body triangle and threatening to turn belly down with it. Crelinsten also has great success by putting his choking hand deep into the opponent’s armpit to hide it from the opponent’s handfighting, then creating a roll or rocking the opponent across to the opposite hip and sneaking the choking hand from armpit to around the throat while in transition. He did this to score the choke on Orchard in the final. And crucially, where most grapplers focus on having a “choking hand” and a “control hand” from the back—one over the shoulder and one under the shoulder—Crelinsten does a great job of working both hands above his opponent’s shoulders and threatening with the choke from both sides, constantly switching.

The Dead Orchard

Our goal here has been to explore some of the ways that striking changed (or punished) the habits of elite grapplers at CJJW 2022, not just highlight the finishes, but I would be remiss to not mention the terrific performance of Nathan Orchard who got to the final with two Dead Orchards and an armbar. More than that, he continues to upset the general consensus that rubber guard is silly.

A favourite criticism of Eddie Bravo’s 10th Planet Jiu Jitsu back in the day was a lack of successful competitors, but between Jon ‘Thor’ Blank, Keith Krikorian, Grace Gundrum and others that critique is clearly outdated. A more valid criticism is that rubber guard is a great way to destroy your knees and seldom seems to work even when applied by the best rubber guard players. But you know what else doesn’t work anymore? Armbars from the guard. At the risk of this article becoming more poorly disguised Charles Oliveira propaganda, he is perhaps the only man using the armbar from closed guard routinely in MMA—and he hasn’t scored a single submission with one, he just throws it up to make the opponent do something else.

The problem with armbars from guard is that they are at their best in the middle ground between the opponent being postured up, and safely postured down laying on top of the guard player. Think of Mark Coleman taking a breather with his elbows on Fedor Emelianenko’s chest.

Nathan Orchard’s “dead orchard” is remarkable because it allows him to score armbars from the closed guard with the opponent fully slumped down on top of him. By figure-fouring his legs along their shoulder line, he can pinch their elbows into the centre of his chest and put them in that in-between posture they would otherwise avoid like the plague. While Orchard hit two on this card, Ben Eddy also scored a dead orchard in his super fight, and Orchard’s third submission—a more traditional overhook armbar from guard—happened because his opponent was trying desperately to posture up with his hands on the mat.

Sure, it relies on some physical attributes that many people don’t have, but this is an athletic pursuit. Find an already high level MMA fighter who can learn how to do it, and you might be able to make him into one of the sport’s few submission threats from the bottom. In any case, plenty more happened at the Combat Jiu Jitsu Worlds 2022 and even I, as an embittered EBI supremacist, am still telling you to check it out on UFC Fight Pass.

If you’re in the mood for more martial arts technique analysis, check out my Dustin Poirier Advanced Striking study, and Anderson Silva for good measure. Or keep an eye on the Patreon for the odd Sunday when I feel like writing a UFC post fight breakdown.