If you didn’t know Chan Sung Jung was special, you need only look at the reactions to him getting knocked out flat on his face on Saturday night. Jung requested a fight that few thought he had a chance of winning, but when he saw he didn’t have the speed or the skills to keep up with Max Holloway he made the decision to chase Holloway down and make a brawl of it. It was a valiant choice in a sport where—whether they mean to or not—older, slowing fighters become more tentative. It is often speculated that the reason so many fighters are slow to see their own decline is that they make it to the losing end of several lopsided decisions rather than getting completely obliterated.

From a tactical perspective the bout was a masterclass in defusing the counterpuncher. The Korean Zombie has a great eye and anticipation, and even as recently as his December 2021 fight with Dan Ige he has shown that if all you have is speed and power he will read you and he will still beat you to the punch. Holloway was able to bamboozle Jung with feints and non-committal strikes.

The body jab was demonstrated masterfully by Holloway who is still one of just a handful of fighters making use of it in MMA today. The risk : reward obsession of MMA fighters painted the body jab as a nothing punch that came with the risk of getting kneed or uppercutted in the head while changing levels. Jose Aldo’s counter knee knockout against a body jabbing Rolando Perez was the standard example. Of course, Holloway later fought Aldo and used the body jab to vex and tire the then champ, and did it such a non-committal way that he would look at Aldo’s body and shrug a shoulder and Aldo would whiff on a booming uppercut or knee strike, only to leave himself out of position and a little bit more tuckered out.

Holloway poked Jung with the body jab, and any time he suspected The Korean Zombie was getting the read on him, he’d feign it instead. Jung would thrown a big left hook or right uppercut and then have to rush to get back in position to defend himself.

The body jab is a multi-faceted attack. On the surface it is an annoyance and, if left alone, it can drain the opponent. Beneath that it can be used to draw counters for very little commitment: a body jab can be feigned or even half completed and abandoned and the fighter is still down behind their lead shoulder. Drawing counters that amount to nothing is saps opponents, but drawing counters with the body jab also makes combination punching off the body jab more lethal. Because the opponent is punching down, the openings in his guard are more pronounced. Whether you come up with a right straight, a right overhand, or a left hook, all take advantage of the opponent punching down.

Figure 1 shows Holloway attacking with the body jab, and Jung attempting to counter with a left hook. Holloway scores the body jab and ducks the left hook.

Fig. 1

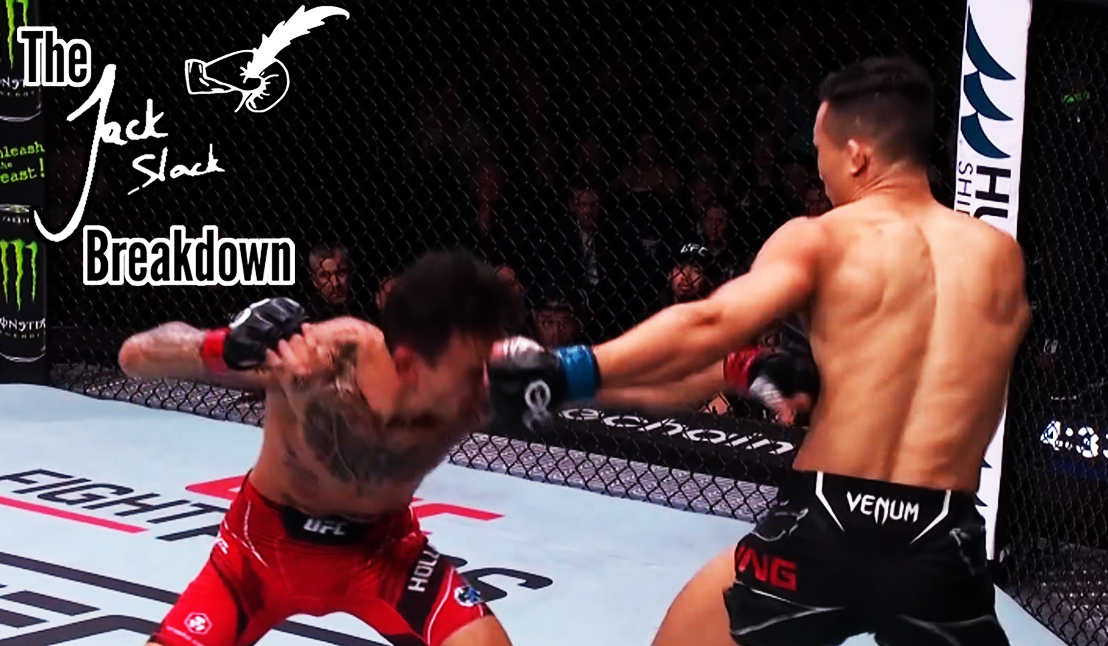

Figure 2 shows the knockdown in the second round as Holloway attacks the body jab, gets under the counter left hook, and follows up with a flicking jab into a right straight. Jung’s powerful counter left hook missing carried him out of position and you will notice he is nowhere near his guard when Holloway is flicking out the one-two.

Fig. 2

The observant reader might notice that the first example is actually from later in the fight than the knockdown. That is because The Korean Zombie was not really in the wrong in looking for his counter left hook. The left hook against the body jab can be a very good read. Holloway is down behind his left shoulder and that makes landing right hands across the top difficult. Counter uppercuts offer bigger openings for Holloway if he only fakes the jab or if the counter uppercut misses. The left hook goes in on the open side, where Holloway’s right hand is the only obstruction. This brings us to a theme from Saturday night: leverage guards or frames and the importance of playing the position. Holloway didn’t get left hooked in his body jab because he was actively seeing it and ducking it.

Anthony Smith wasn’t body jabbing against Ryan Spann when he got hurt, but he was framing and down behind his lead shoulder. It is a position that fighters learn to use and then feel comfortable because it shields them from the big right hand. But by using it as a static moment of safety Smith failed to see Spann’s left hook coming and took the brunt of it square on his left eyeball. Notice that even if Smith had his right forearm up in (b), it would be the width of his wrist shielding him from the width of Spann’s fist. Static guarding is never truly safe, even when using slicker leverage guards or frames. While Smith went on to win the match, it was one of the most telling connections and changed the flow of the fight considerably.

Fig. 3

Another example of the importance of framing can be seen when comparing Chidi Njokuani’s use of the inside low kick to other fighters on the card. Perhaps because Alexander Volkanovski made inside low kicking sexy again, everyone is rediscovering the move. But if you remember Gaethje vs Poirier 1, the inside low kick doesn’t often buckle the opponent’s stance and leaves you standing in the path of their power hand. Gaethje learned from the first fight and threw a total of zero inside low kicks against Poirier in their second, but across the UFC we seem to be experiencing something of an epidemic: fighters scoring a big beefy kick to the inside of the thigh that ultimately only stings a little, and getting brained for their trouble. Billy Goff showed an open stance example, kicking with his rear leg to the inside of Yusaku Kazushita’s lead leg and getting hit with a left straight, Figure 4.

Fig. 4

And Toshiomi Kazama demonstrated the closed stance variation, throwing a step up lead leg inside low kick against Garrett Armfield. This was especially Gaethje-like because he was getting boxed up and threw in the inside low kick as if it were somehow going to end the fight. As Hail Mary techniques go, the inside low kick falls short.

Fig. 5

Contrast those with Chidi Njokuani, who used the inside low kick as a balance breaker against Michał Oleksiejczuk. Oleksiejczuk is a southpaw whose striking is entirely built around his left hand. Oleksiejczuk was trying to catch Njokuani along the fence and in Figure 6 you can see Njokuani switch to southpaw to match Oleksiejczuk. Oleksiejczuk steps in for a overhand and Njokuani meets him with a frame (b), raising his lead shoulder and hiding his chin. As Oleksiejczuk throws himself onto his lead foot and the left hand flies in, Njokuani hacks that foot out and ducks further down behind the line of his shoulder. Oleksiejczuk falls to the mat and Njokuani is left unhurt.

Fig. 6

The two key differences were:

1) that Njokuani used his inside low kick to counter the opponent’s rear hand, not as a stand alone technique that left him on one leg in the path of it.

2) that Njokuani used frames and dipped his head below his shoulder line to keep himself safe.

The Oleksiejczuk - Njokuani bout was far better than I expected and their styles matched up in compelling ways. Njokuani wanted to kick and circle, while Oleksiejczuk wanted to walk Njokuani to the fence and stick to kicks, following them back with the overhand. Figure 7 shows an example of Oleksiejczuk parrying a kick, or really just holding it in place as he swings over it.

Fig. 7

Njokuani was able to exploit the keenness with which Oleksiejczuk tried to parry kicks. In the very opening moments, Njokuani threw a number of front kicks and round kicks to the body and both of Oleksiejczuk’s arms came across to meet them (Figure 8).

Fig. 8

This is not a case of bad form, it is just that fighting is a tit-for-tat affair. You defend one technique and you open up another. Figure 9 shows how Njokuani faked with a right knee raise (b) and stepped through to grab Oleksiejczuk (c), skewering him with a left knee to the liver (d). Finding the liver can be difficult for an orthodox fighter against a southpaw but notice how far Oleksiejczuk’s right elbow has been drawn across his body by his own defensive work.

Fig. 9

Njokuani used a right collar tie and a left grip on the elbow throughout this fight to score knees. Figure 10 shows how Njokuani was able to turn Oleksiejczuk and land two more knees off the pivot.

Fig. 10

You will notice that in frames (e) and (g), Njokuani has passed Oleksiejczuk’s elbow almost all the way across his body, clearing the path for the knee strike behind it. This blocking the elbow and circling around behind it is as much wrestling as it is Muay Thai. Here’s Nathan Tomasello hitting a gorgeous inside reach single leg off an elbow pass. Getting behind the opponent’s elbows is a winner in all martial arts.

Sadly, Njokuani is not such a force on the ground as he is on the feet. He was taken down off a caught knee strike and suffered a TKO which might nullify all of his successful kneeing in the minds of many fans. As with every other interesting leg strike, we patiently await the day that it catches the eye of the kind of wrestler who can afford to give up a leg without it being a fight ender.

Returning to the Holloway - Jung fight for a final thought: Holloway had great success with the weaving left hook on a couple of occasions. Figure 11 shows the move in action. This is the kind of technique where you benefit enormously from getting your opponent to throw back. It is a strike which works best if you start a gun fight and then slide out the side door. Holloway shoulder fakes his right hand (b), steps through into southpaw (c), and weaves under Jung’s left hook, scoring his own as he rises out of the weave (e).

Fig. 11

Long time fans will remember T.J. Dillashaw knocking out Renan Barao with this in their second fight, or Kyoji Horiguchi using it against fighters like Neil Seary and Manel Kape. Horiguchi used it after bursting in out in the open: his opponents so seldom got the chance at a good trade that they would immediately swing and allow him to thread himself under and score it. Dillashaw and Holloway showed the more realistic application for most fighters. The best time to force a trade is when the opponent has his back to the fence and he is like a cornered rat: ready to bite down on his mouthpiece and take a stand.

A final thought for J.J. Aldrich who put on a good showing with some interesting looks, but mainly gets mentioned here for momentarily becoming a 125 pound, redheaded lady Brock Lesnar. Figure 12 shows her use of the stockade, as Lesnar made famous against Frank Mir.

Fig. 12

Aldrich pins a hand to the floor and wraps Liang’s head (a). She forces her left hand into Liang’s armpit (b) and by punching her fist into the floor and raising her elbow, she creates pressure on Liang’s neck and raises her left arm to the point of ineffectiveness (b) (c). This also turns Liang onto her side. This is great because Liang now has both hands occupied: one jacked up with the stockade and the other hugged behind Aldrich’s torso, while Aldrich has one hand free to punch.

For a lineup that did little to inspire excitement ahead of time, UFC Fight Night - Singapore was honestly a bit of a treat for the technique head.