Advanced Striking 2.0 – Igor Vovchanchyn

When Igor Vovchanchyn stepped into the ring for the quarter final of the PRIDE 2000 Grand Prix in Tokyo, he had something of a home field advantage. Not in the traditional sense, he was a Ukrainian born, raised in, and fighting out of Kharkiv. But for Igor Vovchanchyn this fight marked the beginning of his eleventh one-night tournament. One commentator for a Vovchanchyn bout in Israel three years earlier had put it best: “Igor doesn’t need to fight in tournaments any more—he could take superfights—but he wants to.”

The tournament fighter is a peculiar breed. To see the highest level of fighting you take two competitors and their teams, you tell them when they are fighting, and you give them time to prepare. Tournaments do not result in the best gameplans and performances, but they are perhaps the closest to the spirit of all-out fighting. Everyone who makes it to the last round of a one night tournament is injured, and faces opponents they could not possibly have fully prepared for. There have been a few great tournament fighters in kickboxing—Semmy Schilt most notably—but in MMA, there is no tournament fighter more prolific than Igor Vovchanchyn.

Fig. 1

Vovchanchyn was notable for being one of the first consistent knockout artists in mixed martial arts, and for succeeding as a striker in a landscape dominated by grapplers. But so much of Vovchanchyn’s success lay in attributes that led him to excel specifically in the tournament structure. The first was his tremendous conditioning. While Igor started out as a lean 190 pounder, and bulked up to a thicker 220 pounds, he was able to keep pace through a gruelling thirty minute bout, drink some water and have a lie down backstage, and then come out and do it again against a new opponent. His run through IFC 1 is a perfect example of this. Vovchanchyn fought three giants—the smallest of whom outweighed him by seventy pounds. Each of these men soon tired, and the last place you wanted to be standing still was in front of Igor Vovchanchyn.

A second fascinating part of Vovchanchyn’s make up was not only a refusal to lose, but a refusal to be made powerless from any position. Vovchanchyn fought in an age when giving up the mount often resulted in a submission just due to the hopelessness of the situation. But Vovchanchyn was taken down, mounted, gave up his back, got pinned underneath stronger fighters for minutes at a time, and still found a way through. It was not even necessarily that he escaped or reversed his opponents. At IAFC 1 in Israel, Vovchanchyn fought a gruelling forty five minutes to get to the final, where he met the American wrestler, Nick Nutter. Nutter had dispatched his two opponents in five minutes each and was obviously the fresher fighter. Nutter easily took Vovchanchyn down and rained strikes upon him against the fence. Yet after ten minutes, Vovchanyn had broken Nutter’s nose from the bottom with headbutts, and completely exhausted the wrestler to the point that he submitted while—to all appearances—being in complete positional control of the fight. The two met in the finals of another tournament, four months later, and Vovchanchyn left Nutter unconscious off an intercepting knee in fourteen seconds.

The striking style of Igor Vovchanchyn was characterized by its wide swings. While he and Fedor Emelianenko had little to do with each other aside from being born in Ukraine, both were known for a long, open elbow style of swinging. In the 2000s, because of Emelianenko’s success this became a source of fascination and began the myth of the “casting punch” of combat sambo. In truth it seems like more of a boxing acquisition than a sambo one. Reviewing the mechanics of the Soviet Union and the United States teams through Olympic boxing during the cold war, there was a noticeable tendency for Western fighters to hook with the palm facing towards them and the thumb up, while Soviet fighters were more likely to hook with the palm down or even turned over to look at their watch. That period was an arms race in amateur boxing coaching and strategy and through the sixties and seventies, and to make a sweeping generalization: United States boxers were coached to incorporate more lateral movement and straight hitting, while Soviet fighters were more likely to throw their punches on arcs and in unusual loops. Or to put it another way: US fighters found angles through movement, and Soviet fighters created angles on the blows themselves. Vovchanchyn and Emelianenko both trained boxing under old Soviet coaches and likely acquired the habit in that way.

The advantage of turning the fist all the way over is that it allows a fighter to throw a long swing and for it to actually strike effectively. Attempt a palm-in hook and then try swinging it in with an almost straight arm—at a certain distance from the body, the palm-in hook connects more with the fingers and “door knocking knuckles.” By turning the hand all the way over to “check the time”, a fighter can connect with the back knuckles and—at worst—the back of his hand, protecting his fingers. When fighting bareknuckle the fingers are a major consideration, but even in MMA gloves that specific issue of the fingers connecting first on a long swing is not at all mitigated by the partially open gloves.

It was not always Vovchanchyn’s intention to hit with the padded part of the glove or the back of his fist though. Very often on his wide swings, Vovchanchyn would land with the thumb side of his fist—or a “ridgehand” in traditional martial arts. In a bare knuckle fight with Edson Carvalho, Vovchanchyn dropped the Brazilian three times in quick succession, each time with a swing that connected on the inside of his index finger knuckle. Later in instructional videos, Vovchanchyn would deliberately demonstrate the punch landing in this way. Just as often he would connect with his wrist or forearm, as when he clattered Gary Goodridge over the back of the head with a long overhand (Figure 2). Either way, Vovchanchyn’s long swings connected far further out than the regular hooks of a 5’ 8” fighter should, and it caught everyone he fought by surprise.

Fig. 2

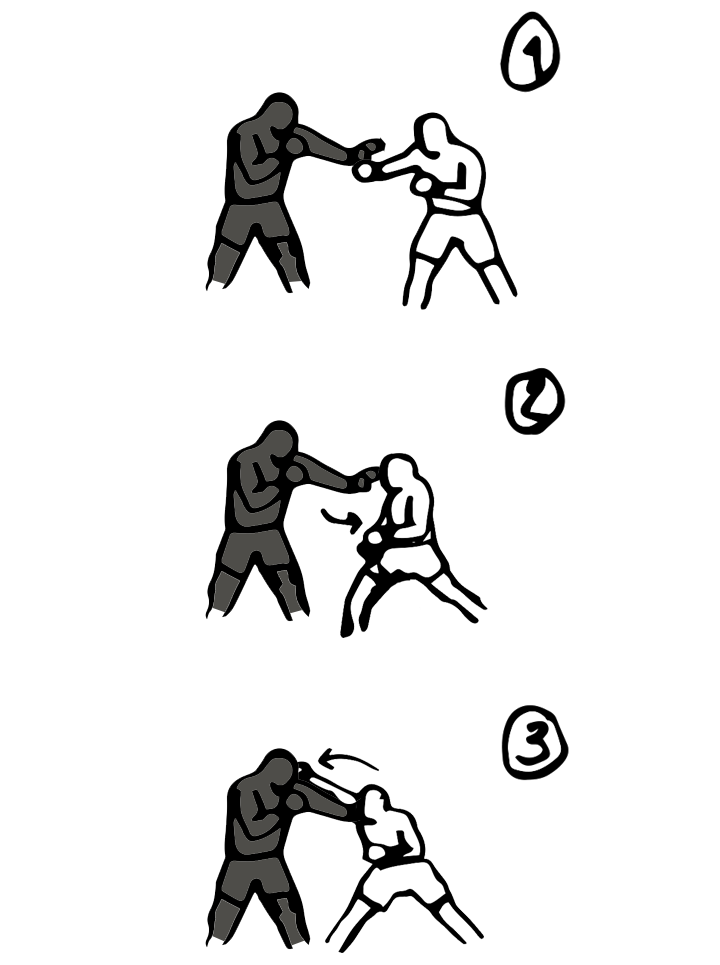

A major part of Vovchanchyn’s game was squaring his feet. A bladed stance is not well suited for two fisted hitting and so in boxing you will commonly see fighters step their right foot in with their right hand, to create a more squared stance and continue rapid fire hitting from both sides. But squaring his feet also allowed Vovchanchyn to weave. There are two ways to “duck” in striking: you can bend at the knees, or you can bend at the waist. A bend at the knees is more commonly called a “bob” or a “dip.” A weave is a bend at the waist, performing a “U” shape with the head to get the fighter under a return. Figure 3 shows an example of Vovchanchyn landing a low kick (2) and weaving his head from left to right as he places his kicking foot down out to the right and slightly in front of him (3).

Fig. 3

Figure 4 shows a classic Vovchanchyn combination that carried him to the inside. Vovchanchyn stood a stout 5’8”, where many of his opponents were well over the six foot mark, so one of the ways that he liked to close the range was walk up and lead with a stumpy right low kick (2). His opponent would inevitably swing back and Igor would duck in towards the centre of their chest (3), weaving his head across and coming up on their right side (4). Vovchanchyn would come out of the weave with a left hook (5), standing in hitting range with his opponent with his feet squared and ready to keep swinging.

Fig. 4

For the crop of No Holds Barred fighters he met, weaving was almost unheard of, but even against talented kickboxers like Masaaki Satake and Ernesto Hoost, the level changes and vertical movement of Vovchanchyn’s game were exotic. The reason that MMA fighters and kickboxers were not trying to learn to bob and weave at the time was the same as it is now: in a sport where kicks and knees are legal, ducking onto a knee is something to be feared. Level changes were a constant feature of Vovchanchyn’s striking though—after he threw a big punch, he would duck or weave out the side. Mid flurry he would level change and pump a couple of short, straight blows to the body before coming up with a left hook. Often Vovchanchyn would throw a right hand with all of his being, duck in after it, and deliberately grab double underhooks on his opponent in a style that Fedor Emelianenko would make famous a few years later.

On paper, as the undersized knockout artist, Vovchanchyn needed space to work. Yet in practice the clinch was a major part of his success. He quickly learned some simple takedowns and would faze stronger grapplers by throwing them to the mat and hitting them with surprisingly crisp arm punches from the top of closed guard. But just as often, against giants in one night tournaments, Igor would use the bodylock to shuck his way behind his opponent. At IFC 1, Vovchanchyn shucked his way behind Fred Floyd and physically could not lock his hands around the big man. Yet Vovchanchyn kept doing it and then throwing in punches from behind the slower, larger target.

The observation that a dynamic hitter needs space to do that hitting was still accurate though. If Vovchanchyn gave up poor position in the clinch, he could be stifled, leaned on, and taken down. Because of this Vovchanchyn was one of the first fighters to demonstrate the value of head position in the MMA clinch. Wrestlers were already aware of the stifling power of good head placement, but as most of them were desperate to close space and achieve the clinch, there was no reason for them to post the head in MMA yet. Each time an opponent closed in, or he and his opponent came together after a punching exchange, Vovchanchyn would post his head against their chest and create space between his hips and theirs. It was then that he could work his hands in front of their shoulders and begin to frame out.

In the No Holds Barred portion of his career, Vovchanchyn was also able to use the knee to the groin to tremendous effect—tagging his opponent with a quick shot South of the border, and then pushing out to swing a thudding right hook over the top (Figure 5). When Vovchanchyn fought Gary Goodridge the second time in PRIDE, he permitted himself to use this thoroughly illegal old school technique once and snapped Goodridge’s cup in half in the process, leading to a halt to proceedings while Goodridge changed into a replacement.

Fig. 5

There is also something to be said for Vovchanchyn’s early use of switch hitting. Today alternating between orthodox and southpaw stance mid fight is a regularly observed skill, but that is among well rounded modern fighters who are confident in wrestling and ground fighting. In Vovchanchyn’s day, learning to stop a takedown off one stance was difficult enough to deter even the most experienced strikers from switch hitting. Vovchanchyn picked his moments to switch stance very well though.

While he had an excellent orthodox left hook and left uppercut / upjab that he would leap up into out of a level change, Vovchanchyn’s southpaw right hook was a different animal. Because it hand to come over the opponent’s lead shoulder, and his opponents were without exception taller than him, Vovchanchyn threw his southpaw right hook in a wide, air guitar style swing so that it came down over the shoulder on a similar angle to his orthodox overhand right. Figure 6 shows the right hook that Vovchanchyn used repeatedly to stop John Dixson. Feinting in with a slight level change, Vovchanchyn could get Dixson to reach for his lead hand, and then windmill it down low, back behind him, and then in over the top to score the connection.

Fig. 6

Even late into his career, attempting to reinvent himself at 205 pounds, Vovchanchyn was able to knock out Katsuhisa Fuji with a classic overhand into a bodylock, and then a stepping southpaw right hook on the break.

While Igor Vovchnanchyn was one of the sport’s first prolific knockout artists, and he fought every moment of the fight with the knockout in mind, he never fell victim to the tunnel vision so many other fighters have. If all Vovchanchyn did was bomb in the overhand and the left hook, he would have been a handful but finished at a much lower rate. Instead, he used lighter shots, straight hitting, and kicks to set up his big blows or to capitalize on his opponents fear of those big blows. We have already mentioned that his level changes into the double unders clinch and straight punches to the body opened up opportunities for the overhand and rising left hook, but some of Vovchanchyn’s best blows were short straights that capitalized on his reputation as the king of the haymaker.

When Vovchanchyn scored his most famous knockout, over Francisco Bueno, it was a wide left swing into a short right straight through the centre of his opponent’s guard that did the trick. A set up he had used a hundred times in bareknuckle fights—substituting the left hook for a wide left slap to protect his hands but line up the right straight on the point of the chin just the same. Another great example came in his second fight with Gary Goodridge.

Though Goodridge is something of a footnote today, he was a frightening prospect in 1999 and 2000 when Vovchanchyn met him. Their first fight was largely Vovchanchyn showing his usual endurance, spending a few minutes underneath Goodridge before getting up and knocking Goodridge out with a level change into a leaping left hook. But by the time of their second meeting, Goodridge seemed to have gotten the read on him.

Each time Vovchanchyn entered with his left hook or overhand, Goodridge would cover up and, as Vovchanchyn ducked into a weave, Goodridge would grab the back of his head and lean on him, bringing up a knee or two at Vovchanchyn’s face. Soon Goodridge was able to drag Vovchanchyn to the mat and, unlike their first fight, he was able to trap Vovchanchyn’s right hand underneath the Ukranian’s back—the classic “One Armed Man” position. Goodridge had obliterated Amir Rahnavardi from this hold as he could throw his left hand without obstruction at the flat opponent. Vovchanchyn, however, summoned the same resilience and stubbornness he had when trapped underneath Nick Nutter. He slipped, he rolled, he squirmed and he eventually freed himself. When the two returned to the feet, Vovchanchyn hit on a stroke of striking class (Figure 7).

Entering with his expected left hook to overhand, Vovchanchyn knew Goodridge would cover up and this time shoved Goodridge away the moment after the right hand landed on his guard (2,3). Vovchanchyn stepped up and threw his right hand again, this time straight up the middle between Goodridge’s forearms (4), before stepping up into a left kick to the body that took the wind out of the stunned Canadian (5, 6). Seconds later, Igor entered with the overhand again and clubbed the flustered Goodridge over the back of the head this time, sending the big man stumbling and picking up the TKO stoppage and his ticket to the next round of the PRIDE Grand Prix.

Fig. 7

While he was always billed as a kickboxer, Vovchanchyn’s kicks were infrequent. When he did use them, it was either to enter from range (with the low kick and weave) or to punctuate a punching combination. Vovchanchyn sent big Paul Varelans to the mat by stepping up into a front kick to the gut that bent The Polar Bear at the waist just long enough for a Vovchanchyn overhand to come crashing through and seal the deal. But otherwise, Vovchanchyn looked uncomfortable with the kicking game.

Vovchanchyn was another MMA fighter with a lengthy kickboxing record that could never be verified, and in fact there was scarcely any footage of him kickboxing. So when K-1 decided to book Vovchanchyn against Ernesto Hoost in kickboxing, he was quickly chopped up by one of the greatest low kickers in history. It was not so much that Igor Vovchanchyn was completely outclassed by Hoost—who he surprised with his speed closing the distance—but rather that he didn’t seem to know how to check a low kick. It wasn’t that he was just too slow but that he was doing the wrong thing. Instead of turning his shin out into the kick, he would turn his knee in and pick his heel up to his buttocks to try and catch the kick on his foot. This has worked from time to time in kickboxing and MMA, but it has little room for error and no discernible advantages over a regular check. Even after the Hoost fight, when he faced Masaaki Satake in MMA, Vovchanchyn was attempting this largely useless check and eating low kicks in the back of the knee and hamstring for no reason.

It was an even stranger quirk of his game because his other answer to the low kick was to step into the kick and time the overhand. And it worked extremely well. In MMA he sent men like Mark Kerr to the mat the moment they tried to test their kicking skills. Even Hoost, kicking with a perfect guard, was bundled off his feet twice by Vovchanchyn stepping in on his kicks. Vovchanchyn was one of the first to demonstrate the power of this counter in MMA, where a loss of footing could mean a whole round spent on the bottom. Once again, the man to take Igor’s idea and excel with it was the great Fedor Emelianenko.

Igor Vovchanchyn’s legacy is often a point of discussion and boils down to what ifs. What if Igor had fought at an appropriate weight? What if he had come along a little later and hit his prime in the golden age of the PRIDE Middleweight division? But Vovchanchyn became an early MMA star because of his feats in his era: feats that could only exist at that precise time. Igor straddled the final days of No Holds Barred competition and the coming of Mixed Martial Arts. His performances in one night tournaments against less skilled giants probably couldn’t have happened at any other time. And as PRIDE FC began, punchers like Vovchanchyn did not exist—not only in terms of power, but in being able to reliably knock opponents out without being tumbled to the mat and submitting from the bottom of mount. Along with the thoughtful Maurice Smith and the better rounded Bas Rutten, Igor marked the breakthrough for “The Strikers” in an era where the wrestlers and grapplers were expected to have the upper hand forever.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————--

Check out the previous entries in the Advanced Striking 2.0 series: