Despite being known as a boxer and a volume puncher, Max Holloway has found ample use for the back kick through his mixed martial arts career. Because Holloway was signed to the UFC at the tender age of nineteen, all of his growth and experimentation has happened under the bright lights, against elite opposition. Holloway’s back kick developed through trial and error, and in his early UFC run he made more bad attempts at spinning attacks than good ones. Without a written rulebook, he came to the same conclusions that most good spinning kickers come to. Generally, the best times to attempt spinning strikes are:

- Against the boundary (ropes or cage).

- On the counter

- As the opponent circles past the lead leg

Each of these scenarios makes a spinning attack more effective in its own way. Attacking against the boundary denies the opponent a retreat. Spinning on the counter reduces the likelihood of the opponent sidestepping or retreating. Attacking as the opponent circles past your lead leg also places him on the line on which you need to spin and shortens the path and telegraph of your high-risk attack.

Make sure to read The Tactical Guide to Ilia Topuria vs Max Holloway before their fight at UFC 308.

Feet on a Line

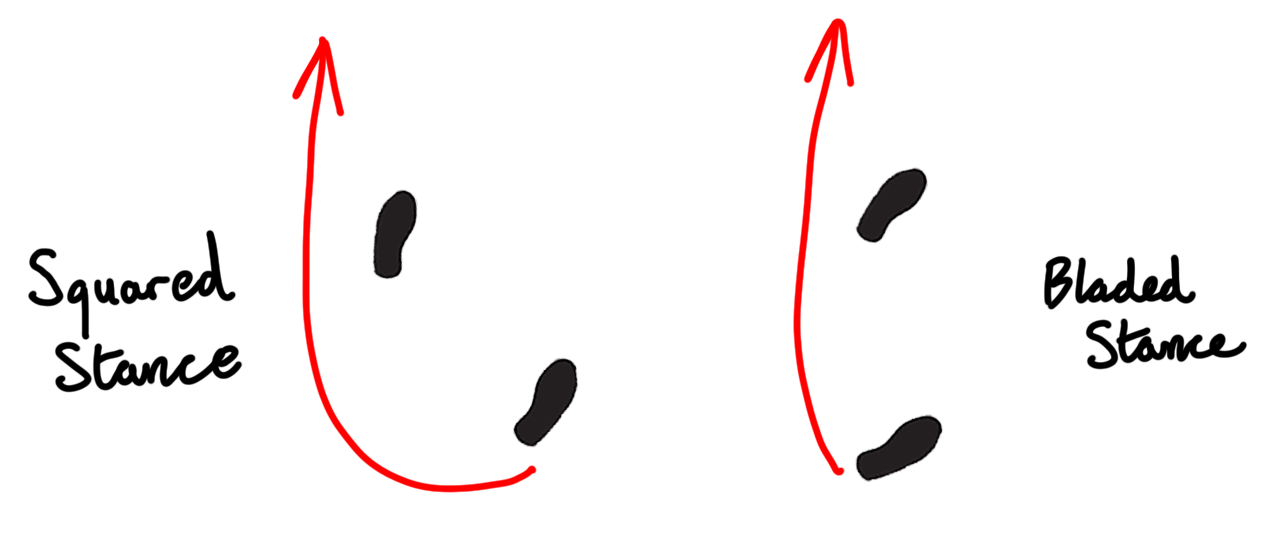

The focus of many young fighters as they learn spinning attacks is on the entry level problem: how do you get your feet onto a line so that you can spin? If you stand in a squared stance, ready to check kicks, you cannot comfortably spin out of your stance because your lead foot is too far off to the side of the opponent’s centreline. Even with the tightest back kicking mechanics, your kick does not land in a straight line above your pivoting leg, but off to the side because it originates on the other side of your hips. Executing a spinning kick from a square stance—against an opponent directly in front—results in a miss down the side of the opponent, exposing the kicker’s back and giving him some work to do to get back in position to defend himself.

Figure 1 crudely demonstrates the value of getting the feet on a line. When standing in a squared stance, a fighter’s rear foot has to travel a much greater distance to even get in front of the line of his body on the spin. In a bladed stance, the fighter turns on the ball of his lead foot and his kick goes straight across the back of his stance. Throwing a spinning kick from a squared stance necessitates an overspin to hit the target if he is standing at twelve o’clock, and overspin results in loss of power and balance.

Fig. 1

Few fighters have success fighting from a bladed stance in sports where low kicks are permitted, so to score spinning kicks a fighter must find ways to move his feet onto a line momentarily. Some simply adjust their stance between exchanges to reengage in a bladed stance, though this is often obvious to an opponent who has been staring intently at them for the entire fight. One way that Max Holloway found to get his feet onto a line and ready to spin was to use his jab and V-step.

The V-step is performed by stepping in—usually to jab—and then rebounding off the lead foot and retreating to either the left or right. If an orthodox fighter retreats to his left on the returning portion of the V-step, he must pivot around his lead leg and cross himself up to some degree to do so.

Fig. 2

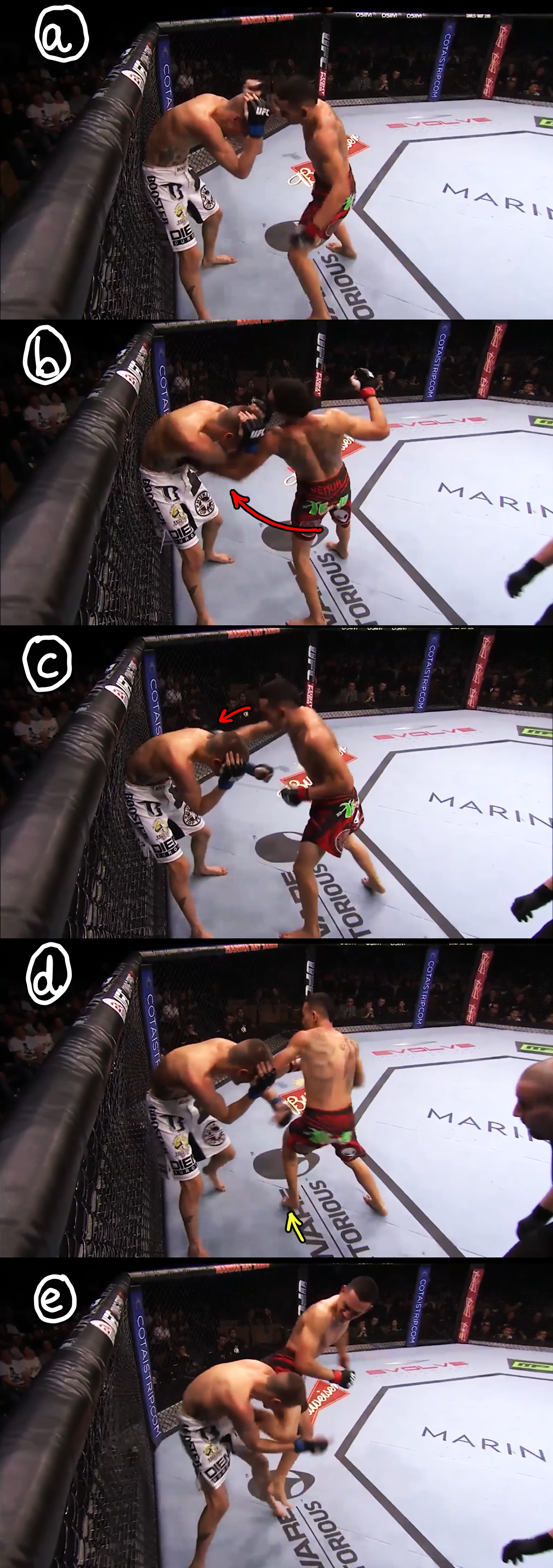

Figure 3 shows an example of Max Holloway’s V-step setting up his back kick. Stepping in with the jab (b), he pivots around the lead foot and retreats back to his left (c). The pivot allows him to get his feet onto a line (d). He waits a beat as his opponent turns to face him and begins to advance, and spins into the back kick.

Fig. 3

This was Holloway’s most successful set up for the back kick through his early UFC career. But he did not limit himself to just this trick, he attempted back kicks and wheel kicks at every stage in the fight. Consequently, Holloway missed a great many spinning attacks and found himself out of position.

Spinning attacks are seen as high risk and high reward, but by limiting himself to the three ideal scenarios—at the boundary, on the counter, and as the opponent circles—a fighter reduces the risk significantly. Advancing back kicks, out in the open, are the type that most often result in failure.

If the opponent has no boundary at his back, retreat is still viable. Figure 4 shows a repeat occurrence from Holloway’s fight with Clay Collard. Holloway obviously telegraphs his back kick with a naked step across himself (b), and as Collard drops back and to the right, Holloway throws himself wildly out of position. This is not disastrous because the opponent has used the space behind him to escape the kick so he is rarely in position to really take advantage before the kicker can get back on guard.

Fig. 4

Spinning when the opponent has a boundary at his back removes his retreat. Spinning on the counter or as the opponent is circling are effective because the opponent is committing to a movement that will keep him in the path and power of the kick. When used as a lead, away from the boundary, spinning attacks give the opponent an easy step down the blind side of the kicker. Figure 5 shows a scenario that happened a few times in both the Benavidez and Swanson fights. Holloway leads with a big step into wheel kick, and his opponent steps out to the other side, staying ahead of the kick and winding up behind Holloway as he is completely out of position.

Fig. 5

For such a big, expressive movement, the success or failure of a back kick can hinge on a few inches in the initial foot placement. Figure 6 shows a great exchange from Holloway’s fight with Andre Fili.

Checking Fili’s lead hand (a), Holloway stabs in with his jab (b). Fili immediately returns and Holloway slides back just far enough to parry the jab (c) and return with a second jab of his own (d).

Fig. 6

The sequence continues in Figure 7 as Holloway follows the jab with the suggestion of a right straight: stepping in, shoulder feinting, but pulling up short (e), (f). Just as Fili begins to come back, Holloway steps across himself (g) and turns into a back kick to intercept Fili (h). You will notice that this successful back kick conforms to two of the three key scenarios: it is along the boundary, and on the counter.

Fig. 7

But look at where Holloway’s kick lands. One of the reasons the back kick can be used as a devastating counter—even when delivered with a hop and taking away much of its power —is that it tends to land on the liver or solar plexus. A few inches to the Fili’s right in the above example—if Holloway had not stepped across far enough or had under rotated—and Holloway could end up in a much worse spot. Figure 8 shows the difference a couple of inches off center can make in the same scenario.

Fig. 8

Obviously there is the chance that the opponent grabs a back bodylock, but Martin Nguyen’s knockout of Eduard Folayang is a perfect example of just how much trouble the kicker can get into from here.

Fig. 9

Against the Boundary

Holloway has found a variety of creative ways to get his feet onto a line in order to spin, and he shows new ones in almost every fight. When combined with moving the opponent to the boundary, these work even better. Figure 10 shows a terrific set up from his fight with Will Chope. A wounded Chope has backed onto the cage (a) and this allows Holloway to get in and rip to the body with his left hook (b). He swats in a right hand to keep Chope busy (c), then steps across himself (d) and performs the short range, jumping back kick that you will often see in the chest-to-chest exchanges of Kyokushin karate (e). With his stance flattened against the fence, and in a full cover up, Chope has no choice but to absorb the brunt of the kick.

Fig. 10

The Chope example is about as “at the boundary” as you can get. Chope was squared up, out of his stance, and leaning on the cage. But placing an uninjured, fresh opponent close to the fence will result in one of two reactions: he will circle or he will try to fight his way off. Fighting his way off keeps him directly in front of Holloway, meaning the back kick is still viable and it will in fact become a counter. Circling is almost always the smarter option for the man along the fence, and it helpfully sets up an even swifter back kick.

Figure 11 shows how the opponent’s lateral movement changes the viability of the back kick, and spinning attacks generally.

Fig. 11

When the opponent circles away from the kicker’s lead foot, spinning attacks that use the lead foot as a pivot are pretty much impossible. When the opponent circles towards and past the kicker’s lead foot, he places the kicker’s feet on a line with him. The opponent has shortened the spin and reduced the need for a clever set up. With no telegraph on the kick, and the opponent circling into its path, this scenario can result in some of the most devastating spinning connections. It is also one that can be forced against elite fighters because it punishes them for doing the correct thing in trying to circle off the boundary.

Of the three key scenarios, catching the opponent circling is Holloway’s least used. It made a good number of appearances in his second fight with Alexander Volkanovski, because Volkanovski kept circling past Holloway’s lead foot out in the centre of the cage. This allowed Holloway to time several good back kicks by putting a lead on Volkanovski’s predictable movement.

Fig. 12

Another example that might count is Holloway’s back kick along the fence against Frankie Edgar. This was notable as it involved a shift but resulted in a back kick from the original stance. Figure 13 shows the details.

Holloway presses Edgar towards the fence (a), and steps forward with his lead foot as he pitches a right straight (b). He shifts into a southpaw left straight but steps wide out to his right side (c). Edgar has already begun circling out, but Holloway brings his left foot up to put his feet on a line and set up the back kick anyway (d).

Fig. 13

On the Counter

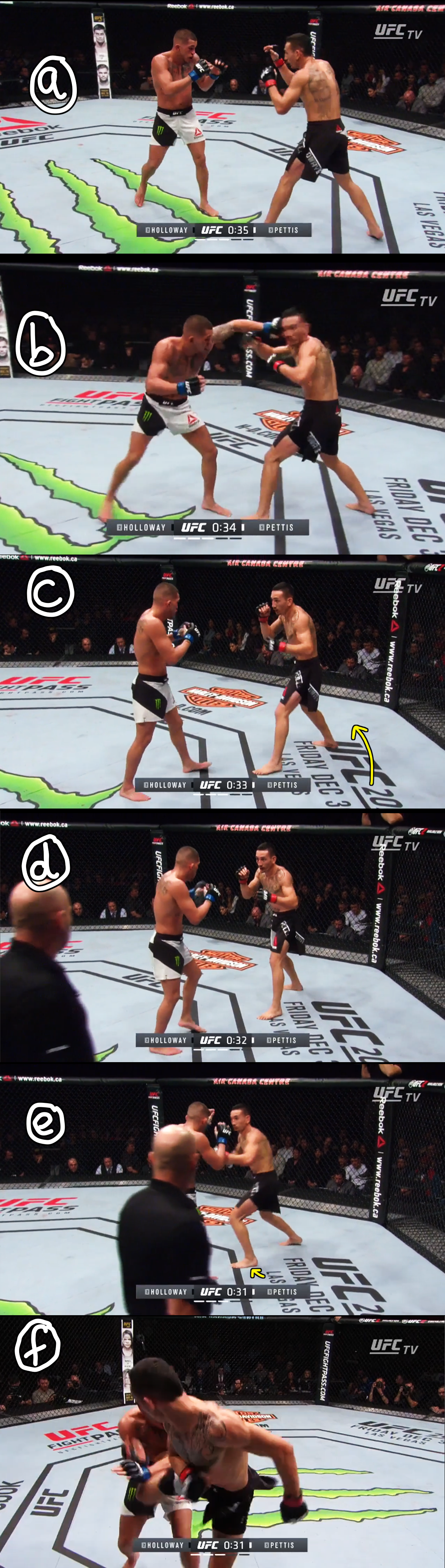

The back kick for which Max Holloway is most famous is the counter back kick. If he is not the best in the world at this technique, he is certainly the most consistent. This counter back kick won him his first UFC belt in an interim title fight against Anthony Pettis. Pettis came up off the floor in the third round and pressured Holloway, who gave ground and ate a jab (b). Holloway circled (c) and as Pettis walked right up to him (d), Holloway stepped across himself and spun into a back kick that winded Pettis.

Fig. 14

Exiting this exchange, Holloway was able to feign a back kick by stepping his lead foot to the middle and turning his shoulders, and then return with a right straight that stunned Pettis and began a flurry that would result in a TKO.

Fig. 15

One of Holloway’s earliest reliable techniques was the counter left hook, which he used to rattle Pat Schilling, Justin Lawrence and Leonard Garcia in his first three UFC victories. Against Dennis Bermudez he began using this counter left hook to get his feet on a line as he retreated out of exchanges. Often the left hook would miss, but would carry him into the short, jumping counter back kick. Figure 16 shows a terrific example from the Bermudez fight where Holloway caught Bermudez in the head.

Fig. 16

This is a peculiarity of the counter back kick. The short jumping back kick, with the heel almost coiled to the buttocks, works well because it tends to land with the heel to the floating rib and liver, or the solar plexus. The fighter is not throwing himself forward as in an advancing back kick, and he removes himself from the floor to spin faster, but the placement makes up for it. Yet there is a tendency among fighters to duck down to the side of their power hand. This natural reaction hides a fighter below the line of his lead shoulder and in a fight between two orthodox fighters will carry the ducking fighter away from the opponent’s right hand.

Yet a fighter who consistently ducks his head down to his right side can double the effectiveness of his foe’s back kick. There were a couple of notable examples that seemed like lightning in a bottle—Uriah Hall vs Gegard Mousasi, Renan Barao vs Eddie Wineland—but the more Holloway uses his counter back kick, the more opponents he catches in the head.

Most recently, Holloway broke Justin Gaethje’s nose in the first round of their fight by countering Gaethje’s attempt at a last minute flurry to steal the round. Figure 17 shows an example against Clay Collard. Holloway has Collard along the fence (a), fakes a lead (b), and then slides back to get his feet on a line (c),(d), and counters with a back kick that hammers Collard in the side of the head as he ducks (e).

Fig. 17

Holloway’s transformation into an extreme volume fighter has allowed him to use his back kick even more effectively. His opponents do not expect to outpoint him and so look for the knockout punch whenever they can. This means that Holloway can back out of a combination knowing that there is a great chance his opponent charges straight at him and he can score the counter back kick. His terrific pace and overwhelming volume force his opponents to cover up by the mid point of a five round fight and this enables him to set up cross steps into offensive back kicks more easily.

Holloway is not a flawless back kicker, far from it. Against Arnold Allen, Holloway continued to look for orthodox spinning kicks against his southpaw opponent and repeatedly hit only Allen’s lead arm and shoulder. He worked out that he might be able to sneak a backfist over Allen’s lead shoulder, or step through and back kick from southpaw himself but he never abandoned the failing back kick.

Fig. 18

One overarching theme of this series is going to be Max Holloway’s fearlessness and willingness to experiment. Many fighters get into the UFC on a talent and work to shore up their weaknesses. Max Holloway has continued to develop new assets and strengths to this day. He learned to back kick by doing it against the best fighters in the world. He learned to fight southpaw by doing it against the best fighters in the world. The fact that every next opponent is a serious threat can stop a fighter from growing, and yet Holloway has managed to use these fights as a laboratory.

———————————————————————————————————————

Part 2 of Max Holloway: The Master Study coming soon!