Poirier vs Gaethje 2:

The Tactical Guide

Their original fight was brutal, but the realization that Dustin Poirier and Justin Gaethje first fought five years ago is a gut punch of its own. The match up rings with familiarity, it feels as though this rematch was an inevitability and we just had to get some other options squared away first. In some regards it still feels too soon, but a lot can change in five years and—for both Poirier and Gaethje—positive change has been a hallmark of their MMA careers.

In examining this rematch it is impossible to overlook that Poirier dominated the first for a couple of reasons: Gaethje’s poor strike selection and strategy, and Poirier’s jab and volume.

The Dumbest Kick

The tactic that Gaethje beat into the ground in the first fight was a single move: the inside low kick. Against orthodox opponents he had found great success pounding the outside of their lead leg with kicks off his rear leg. Numerous low kick TKOs can attest to the fact that Gaethje kicks like a mule. The problem with his approach against Poirier was that he focused on the strike because it was how he threw his leg hardest and not because it was the best weapon for combating Poirier’s stance and style.

Outside kicks can buckle the knee inwards and jar the knee joint. This is a common point in both the traditional kick to the thigh and the calf kick. Kicks to the inside of the leg are painful, and can break the opponent’s balance by spreading his feet apart, but they do not typically jar the knee in the same way. Furthermore, if the opponent stands in a more extended, bladed stance the front of his leg is angled into the kick making that agonizing inner thigh connection even harder to achieve and putting him only a slight leg lift away from a perfect check in a shorter space.

The key exchange that played out a dozen times in the first Poirier – Gaethje fight was Gaethje throwing his right low kick with all his might, scoring it on the inside of Poirier’s lead leg, and getting punched in the face anyway. Often Gaethje lifted Poirier’s leg clean off the mat with the kick and Poirier could still hurt him with a “partial punch”.

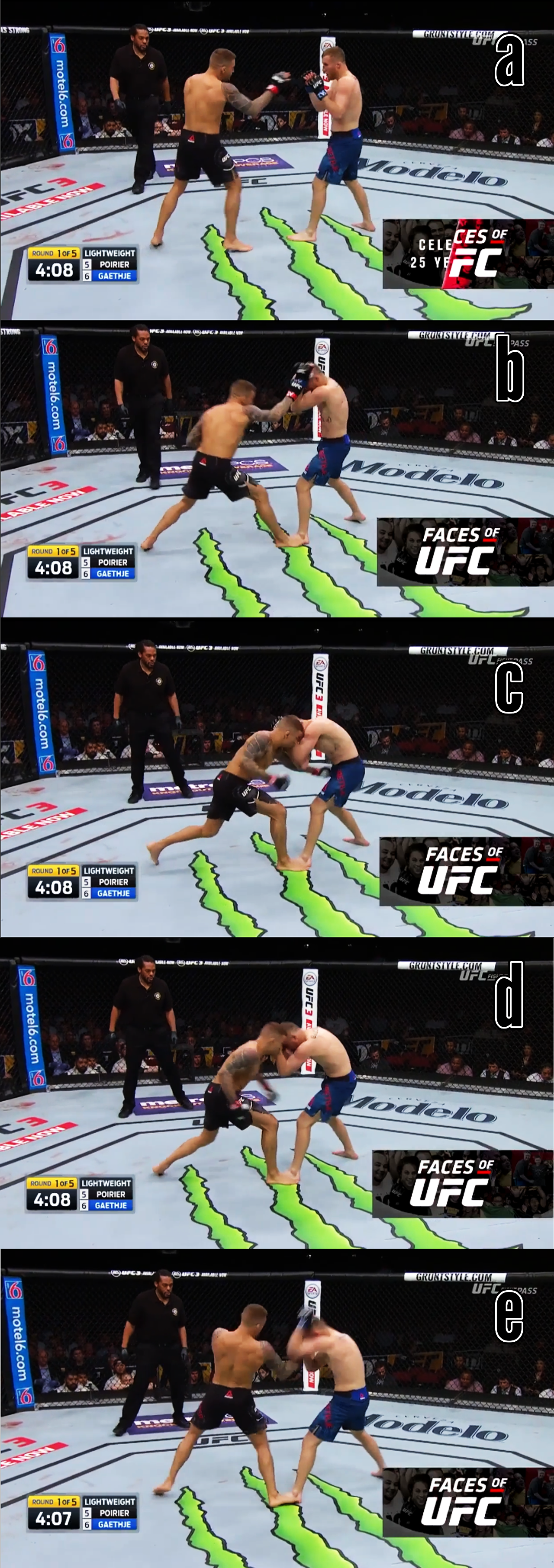

Fig. 1

When Gaethje threw this low kick in the opening of the fourth round, Poirier found the counter once again and followed up to score the finish.

Fig. 2

Open stance inside low kicks are not worthless, but they are a low reward weapon and Gaethje was fighting as if any single kick could stop the fight. He never used the kick to further any of his other weapons, even when he knocked Poirier off balance and out of stance. The only occasion that he built off the blow came at the start of the second round, as he feigned a kick and stepped through to hit Poirier with a couple of punches along the fence. He never returned to this idea though.

This inside low kick is difficult to use in an effective double attack with the body and head kick because the distance is significantly different. It can be done—Leon Edwards was using all three in tandem against Kamaru Usman a few months back—but it takes good hip mobility, convincing feints, and a frequent use of the high kick and body kick, which is perhaps the biggest sticking point for Gaethje.

Right high kicks and body kicks against southpaws are higher reward techniques but they can also, paradoxically, be lower risk because throwing up power kicks on the open side forces the opponent to keep their guard and hold back on counter punching. Bringing kicks above the waist to this rematch would enable Gaethje to step forward into punching exchanges off his kicks, but it does run up against the issue that Poirier will happily grab a leg and threaten to wrestle Gaethje as he did in the first fight.

Variety vs Habit

The secret to Dustin Poirier’s success is that behind his reckless swings and the way that all of his fights become Fight of the Year type brawls, he can keep himself safe when he needs to. As we examined at length in Dustin Poirier - Advanced Striking 2.0, his dilligent work to develop a shoulder roll has enabled him to work more time in the pocket and in turn develop his eyes and his comfort under fire. Justin Gaethje, at least when they first met, was the polar opposite. His offence was frantic to preclude his opponent from testing his shoddy defence.

Gaethje’s vision on the outside was poor and Poirier immediately got to work with his jab. If Gaethje had ever planned to use his own jab, he promptly abandoned that idea when Poirier’s started landing. Instead Gaethje loaded up on left and right swings, which only fed into Poirier’s jabbing. Figure 3 shows Poirier shooting an easy southpaw jab down the inside as Gaethje loads up and charges in behind his face. The moment Poirier’s jab lands, he assumes his high elbow stonewall guard (e) to see off any follow up.

Fig. 3

Gaethje’s overreactions made Poirier’s jabbing even easier. When he wasn’t simply going to a double forearms guard, Gaethje could be made to overcommit in his attempts to parry Poirier’s jab. Figure 4 shows a simple double pump jab that Poirier used throughout the fight: beginning the jabbing motion, cutting it short, withdrawing the hand and firing the jab for real. Gaethje’s reaches meant that the second jab almost always had a clear path.

Fig. 4

It was Gaethje’s cover up that allowed Poirier to pile up the points and accrue damage. At this stage in Gaethje’s career the bull guard and counter low kicks had been more than enough for Gaethje to excel. Poirier’s movement, and counters to the low kicks meant that Gaethje was struggling to break Poirier down, and when Poirier began punching in combination, Gaethje would handcuff himself by going to the high guard and crunching over. One of the shots that Poirier looked for repeatedly because Gaethje so predictably crunched into a shell was the lead hand uppercut, Figure 5.

Fig. 5

Hypothetical Gameplans

Part of the intrigue of this rematch is the growth that Justin Gaethje has experienced. The first fight came immediately after Eddie Alvarez spoiled Gaethje’s undefeated record, and the two crushing knockout losses forced Gaethje to re-evaluate how he was pissing away his enormous potential in sloppy brawls. Furthermore, Gaethje had an operation to correct his vision which it was easy to see was hampering him. Even if a fighter is being hit, you can normally get a good read on whether he can see the punches coming or not. Gaethje’s complete inability to detect strikes at range, one-size-fits-all cover up, and constant feeling for the opponent all belied an inability to see strikes coming. Certainly his performances since the first fight show a more methodical use of his enormous power, but Poirier has still demonstrated a far more rounded striking game, and mixed martial arts game as a whole.

For Gaethje to do well in this fight, taking away Poirier’s jab should be a priority. More than that it would be good to see Gaethje jab with Poirier. It took him 10 minutes to try jabbing against Rafael Fiziev and in the third round, Gaethje tore Fiziev’s face apart with the quickest, straightest punch in the boxing arsenal. While Gaethje mainly stuck to single shots and admired his work, the jab-and-dip worked very well for him when he attempted it, closing to the collar tie and scoring with that terrific right uppercut he has used throughout his career. Of course, jabbing with a southpaw is a different kettle of fish so Gaethje could be well served to simply commit to stalemating the hand fight.

Without his jab, Poirier is more than happy to lead with his left hand. The single good counter punch Gaethje scored in the first fight came as he controlled Poirier’s jabbing hand, timed a slip of the rear hand, and cracked Poirier over the top with his own right hook. Working to manufacture that exchange over and over could certainly be a boon to Gaethje’s chances.

Fig. 6

Additionally, Gaethje had success with a step up lead leg kick to the outside of Poirier’s lead leg. This, of course, buckles the leg in and left Poirier out of position whenever it connected. The more a fighter wants to jab and box, the more he must place one foot forward, and the more susceptible he becomes to outside low kicks.

Fig. 7

The first fight was also a few years before calf kick “technology” was widely adopted. Gaethje loves a calf kick and if he has committed to mastering the step up calf kick, he could have a field day with it against Poirier. Hell, he could have had better success in the first fight with all the same skills if he just fought southpaw and tried the run up punts with his left leg instead of his right.

For Poirier, the first fight is a great start. All the tools he operated against Gaethje then might well still work. The jab, lateral movement and volume punching should all be a part of his gameplan, though the volume might need to be applied a bit more cautiously if Gaethje’s counter punching is looking sharp. This would be a sharp contrast to how readily Gaethje simply covered up in the first fight.

Poirier scored with a few body punches and kicks: enough that you would imagine he could get away with more. Eddie Alvarez showed how much Gaethje hates being hit in the body and how rapidly it can sap his gas tank. Poirier’s underuse of bodywork was a bit of a surprise even at the time. And in turn, Poirier wilted under the body attack of Charles Oliveira, but to hope for body work from even Gaethje 2.0 is to set yourself up for disappointment.

One facet that cannot be forgotten in the rematch is Poirier’s willingness to wrestle. Poirier wasn’t a state champion or NCAA stand-out, but his commitment to simply grabbing Gaethje’s leg when Gaethje kicked, or ducking into a bodylock when Gaethje punched, sent Gaethje into moments of desperation. Poirier got Gaethje off his feet once in the fight, and Gaethje immediately exploded up to standing again, but it was Gaethje who was puffing afterwards while Poirier just got back to work. For Gaethje, Poirier’s takedown attempts were treated as moments of near disaster, and for Poirier they were almost throwaway ideas.

Add to all of this the fact that the fight is happening in Salt Lake City, a famously tricky venue because of its elevation. Many are quick to point out that Gaethje already trains at elevation, and yet he is the man who seems to have trouble with his gas tank. Others are casting doubt on whether Poirier has spent any time acclimatizing at all. It all seems like an unnecessary layer of complication to a great match up, but that is the point after all. Poirier and Gaethje are in Salt Lake City because none of the UFC’s champions wanted to be and because they are both almost a guarantee of a showstopper, “BMF belt” or no.