The Unorthodox Kicking Game of Shara Bullet

Sharabutdin Magomedov has an uphill battle to win your affection. Likely the first thing you heard about the UFC’s new middleweight striker is that he sucker punched a guy in a shopping mall for the crime of having a girlfriend. Or perhaps you saw him enter an ADCC event and try to start a fist fight after getting easily leg locked. He has suffered from the classic MMA bad boy problem of being unable to compete in the UFC’s main market (under a functional commission) because he cannot get a visa—which is probably something to do with that pattern of behaviour, if not those incidents specifically.

But we must always remind ourselves that Carlos Monzon strangled his girlfriend into unconsciousness and threw her off a balcony, murdering her, yet his fights still hold up as bangers. When you put him up next to that, Shara Magomedov’s character flaws are more akin to simply being a cheeky boy.

Magomedov’s UFC debut is available as a free fight on youtube and is well worth your time.

Establishing the Low Kick

The golden rule of low kicking is obvious to anyone who has ever thumped their shin against a coffee table:

“Kick soft, sensitive things, and don’t kick hard things.”

Good checking—meeting the opponent early in the path of the kick—makes it a bit more nuanced than shin-on-shin, but kicking anything that isn’t thigh or calf meat is an undesirable outcome for the kicker. So to land effective low kicks with minimal risk, the kicker’s job is to make sure his opponent’s lead foot is on the mat.

The two main methods to do this are to:

kick off a punching combination

kick as the opponent steps onto their lead leg

You will probably be familiar with the idea of combination punching into the low kick because it became such a central tenet in Dutch kickboxing gyms in the 1980s and 1990s that it is considered to be the best part of the Dutch kickboxing style. But Shara Magomedov seldom throws one good punch, let alone a combination.

Instead, every Magomedov fight is filled with small retreats. He never runs away, he simply keeps correcting the distance to just a little too far for comfort. He does this so frequently and consistently that his opponent gets into the habit of trying to recorrect that distance and get close enough before they begin to attempt their own offence. After he has caught their timing stepping forward, he hammers the lead leg just as they plant it.

Another layer to this set up is that Magomedov will spend portions of the fight circling around, past his opponent’s lead leg. They are then tasked with both following and turning to face him. As soon as an opponent goes outside the fighter’s lead foot, he must pivot around that foot to face them—weighting it momentarily and taking him further away from picking his leg up to check.

If you strip away all the variety in his kicks and his interplay between orthodox and southpaw stance: this is the essence of Shara Magomedov. Movement, distancing, and timing kicks.

This brings us to the most curious aspect of the Shara Magomedov mythos: his eyes. His left eye was always a bit lazy, but early in his career he suffered an injury to his right eye which led to eight surgeries and what The Sun translates as “partial removal.” Michael Bisping was able to compete in the United States by hiding the extent of his eye injury from those famously uninquisitive commission doctors. But the fact that Magomedov has already talked openly about losing his vision will likely complicate getting licensed to fight in the US more than any visa issue.

Yet with one functional eye, Magomedov does not seem to be suffering from a loss of depth perception. As correct distancing is at the heart of his style, you would notice very quickly if he could not accurately read his opponent’s range.

Combining Both Stances

Circling and low kicking does a lot of Magomedov’s work wearing an opponent down, but body kicks and high kicks are an important factor in his fights as well. Introducing kicking variety can be difficult working off a single stance, but Magomedov uses his kicks to switch seamlessly. Take a look at this clip from one of his RCC fights.

Beginning out of an orthodox stance, Magomedov uses a step-up left body kick to retreat back into a southpaw stance. He glides back and as his opponent corrects the distance he scores a powerful inside low kick with his rear leg, but remains southpaw. Then he performs a step-up right low kick to the outside of his opponent’s leg and retreats from the kick to re-establish an orthodox position. Notice that when he retreats to southpaw he cuts an angle back to his left, and when he retreats to orthodox he does the same diagonally to his right. And the really impressive part is that this is a few seconds of a three round fight; Magomedov keeps up this torrent of offense and carefully managed retreat for every minute of every fight.

Being able to fight from both stances means that you can step through or step back out of your kicks rather than having to get back to your base. This enables a fighter to cover and create more distance and is an invaluable weapon for outfighters in MMA. Israel Adesanya and Alexander Volkanovski are very different builds, but both use the step up left kick to retreat themselves into southpaw and change the nature of the stance match up while their opponent is only really concerned about the kick.

Read Israel Adesanya - Advanced Striking 2.0 on the Patreon

An aspect of Magomedov’s kicking game that makes him unusual in MMA is his desire to body kick from exchanging range. You will see this all the time in Muay Thai, but that is a sport where the referee breaks the action if you fall, and allows you to get up. Magomedov tries to slot his left body kick in as a counter, landing high on his shin, with his opponent almost on top of him.

So far these counter body kicks have had the desired effect, slowing his opponents down. The constant hunt for a body kick also opens up high kicks, like the one he used to stun Bruno Silva in his UFC debut. But Shara Magomedov has not fought a good wrestler or ring general yet. Attempting counter body kicks while running backwards onto the fence has a lot of potential to put him in bad spots.

Another solid rule of kicking is that if you kick a lot, you will inevitably miss a lot. That is not necessarily a bad thing—after all if you try to up your punching accuracy by throwing fewer punches you are only going to hurt your chances of winning a fight. But with kicking the dangers of missing are generally greater because you can absorb counters while on one leg, or have a leg caught, or give up a back bodylock. For this reason, Magomedov makes frequent use of the spinning backfist and the side kick.

Both of these techniques work best when the fighter’s feet are in line. When he misses a big round kick, or a has a front kick parried across the centreline, the fighter’s feet are on a tightrope and his opponent is about to come charging in to take advantage of the missed kick. So the backfist and side kick are part deterrent and part trap.

Where’s the Boxing?

Punching is an afterthought for Magomedov. His hands take on the role of framing, and one of his best tactics is to smother the opponent’s punching with the double collar tie. He used this to shut down mid-range exchanges in his kickboxing career, but has adapted it to MMA and now snags the double collar coming off the fence and after defending takedowns.

Like the aforementioned Michael Bisping, Magomedov is not a big hitter. But like Bisping he can wear on his opponent down over rounds and then look for the double collar tie when they cannot put up much resistance. Landing unanswered knees against an exhausted opponent is a clear route to the TKO even if you cannot deck them with one good punch.

You will notice that almost all the clips in the above example began with a long, leaning left hook. He blades his stance and overextends with it, in a way that makes it difficult to continue combination punching if it lands, but landing is normally a happy accident. A collar tie is what he really wants. To see a similar counter punch applied in a more boxing focused game, check out Petr Yan.

But Magomedov has found some other ways to use this long, sloppy punch as well. He can throw it to bring his feet onto a line, setting up the side kick or backfist once again.

Using the same upper body movement but changing the footwork, Magomedov can perform a little run up into his left body kick. This was a favourite of Cub Swanson, and Bas Rutten used it to knock down Katsuomi Inagaki.

So what are Magomedov’s chances in the UFC? Well, he certainly won a lot of fans with his performance against Bruno Silva and his work rate and accuracy did not suffer from the slight improvement in opposition. For most of the fight, Silva was stuck on the end of Magomedov’s kicks, looking frustrated and low on ideas.

Some issues came when Magomedov ran himself onto the fence. This is always going to be the case for an outside fighter, and doubly so for a mobile outside kicker. He needs the correct distance to kick without the risk of eating a punch up the middle, so every time you move to him he will move back. If his ring awareness isn’t completely on point, he’ll soon end up along the cage.

That isn’t the end of the world—in fact, being propped up against the fence might be the best place for Magomedov in order to stay standing against some opponents. The bigger issue is that Magomedov does not use direction changes and fakes when he wants to get off the cage, he just starts trotting around in one direction.

In worse instances he tries to land backfists and big body kicks while his back foot is against the fence. This makes him extremely hittable.

These were flaws that Silva was not able to exploit very well. At several points in that fight, Magomedov hit the fence and Silva cautiously ambled up to him, then backed right off when Magomedov made a half hearted feint at a jumping knee.

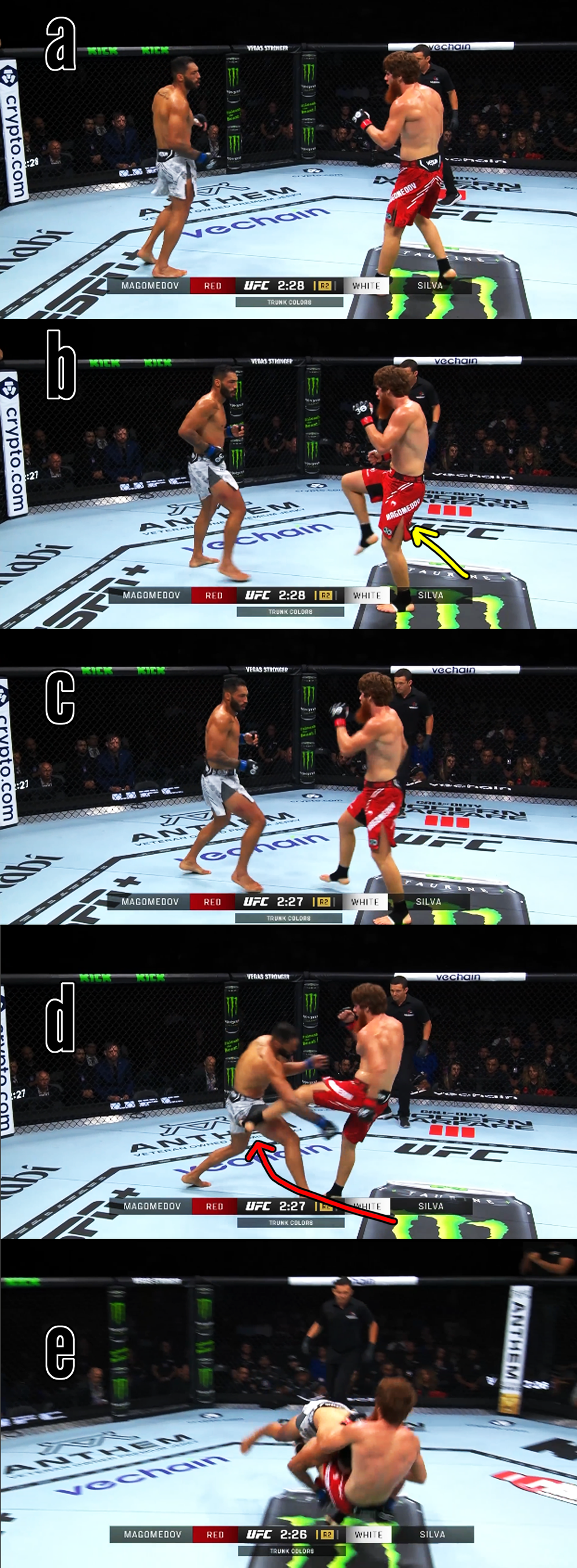

Where Magomedov did get himself into trouble was on a missed read. Pump fakes and marching stance switches are fantastic when the opponent is scared of your kicks and will give ground or freeze up. Here’s an example of Magomedov pump faking by raising one leg, floating in behind it, and scoring the low kick with the other leg.

But the moment the opponent zags when he is supposed to zig, he has fallen arse backwards onto a deep shot at your hips .

Shara Magomedov is unique in MMA. I cannot think of a fighter who kicks with the same frequency and in multi-kick combinations. I would be even more hard-pressed to think of a fighter like that in the upper weightclasses.

But the reason that MMA fighters do not all throw up hatchet kicks, and sling up body kicks while coming out of an exchange off-balance, is that it takes one misread to kick yourself off your feet. This is akin to how I am forever singing the praises of the cut kick in MMA—kicking under a check or kick to sweep out the standing leg. A cut kick in kickboxing or Muay Thai is a cool thing, forgotten after the next exchange. A cut kick in MMA is a free takedown and as much top control as you can manage.

Shara Magomedov botched the same read twice against Bruno Silva and ended up on the bottom for long periods off a takedown that took little strength or technique and was mostly timing. And that was a stand up fight that he was comfortably dominating. He could have another 5 UFC fights without that happening again, but it will always be the central problem for a kick centric fighter. The more you kick, the more you land, but the more time you spend compromising your balance.

Shara Bullet fights on this weekend’s UFC card, alongside fellow Dagestani prospect, Ikram Aliskerov who we gave the deep dive last week.