Tsarukyan vs Gamrot:

Slacky’s Secret Post Fight Notes

Arman Tsarukyan and Mateusz Gamrot fought one of the finest matches to ever grace the Octagon. Elite technique and tactics unfolding at a frantic pace for a full five rounds. Gamrot picked up the decision and that will likely cause some arguments for the week to come, but the bigger tragedy will be Tsarukyan getting half his pay for a performance wherein he and Gamrot battled for openings the breadth of a hair.

To understand the technical and athletic quality of this match up we can draw direct contrasts to the brilliant title fight between Glover Teixeira and Jiri Prochazka two weeks ago. In examining that fight we discussed Teixeira’s use of single legs and how he would off balance Prochazka with a dump attempt, and then use Prochazka hopping on one leg to hoist the captured foot up to shoulder height. At that point Teixeira could run Prochazka down with little difficulty.

Mateusz Gamrot hit great entries onto single legs, off balanced Tsarukyan, hoisted the Armenian’s leg up onto his shoulder, and still couldn’t get him down. This was not just a Tsarukyan talent either. Later in the fight Gamrot spent a good twenty seconds standing on one leg and striking effectively in the process.

Both men working off one leg in what would be a certain takedown in 95% of fights.

Fig. 1

And just as a standout moment in the Teixeira – Prochazka fight was Teixeira hitting a sucker drag from underneath Prochazka’s sprawl, Gamrot was following up on every shot with an attempted sucker drag or elbow pass. The conditioning and discipline necessary to chain wrestle for twenty-five minutes is remarkable, and it paid dividends: even when Gamrot couldn’t get Tsarukyan down, Tsarukyan never got the chance to enjoy simply laying on top of Gamrot or threatening a submission after a failed shot. Gamrot was always attacking again and escaping back to his feet in the process.

Another sharp contrast might be made with Neil Magny in the co-main event—who kicked until his leg was haphazardly caught in Shavkat Rakhmananov’s armpit, and then hopped backwards and fell over himself. Tsarukyan—and to a lesser extent Gamrot—kicked freely and expected to have the leg caught. When his leg didn’t come back clealnly Tsarukyan immediately began defending a single leg, framing off the face, and smashing in punches and elbows. If he had second guessed his kicking he wouldn’t have had half the success he enjoyed in this fight.

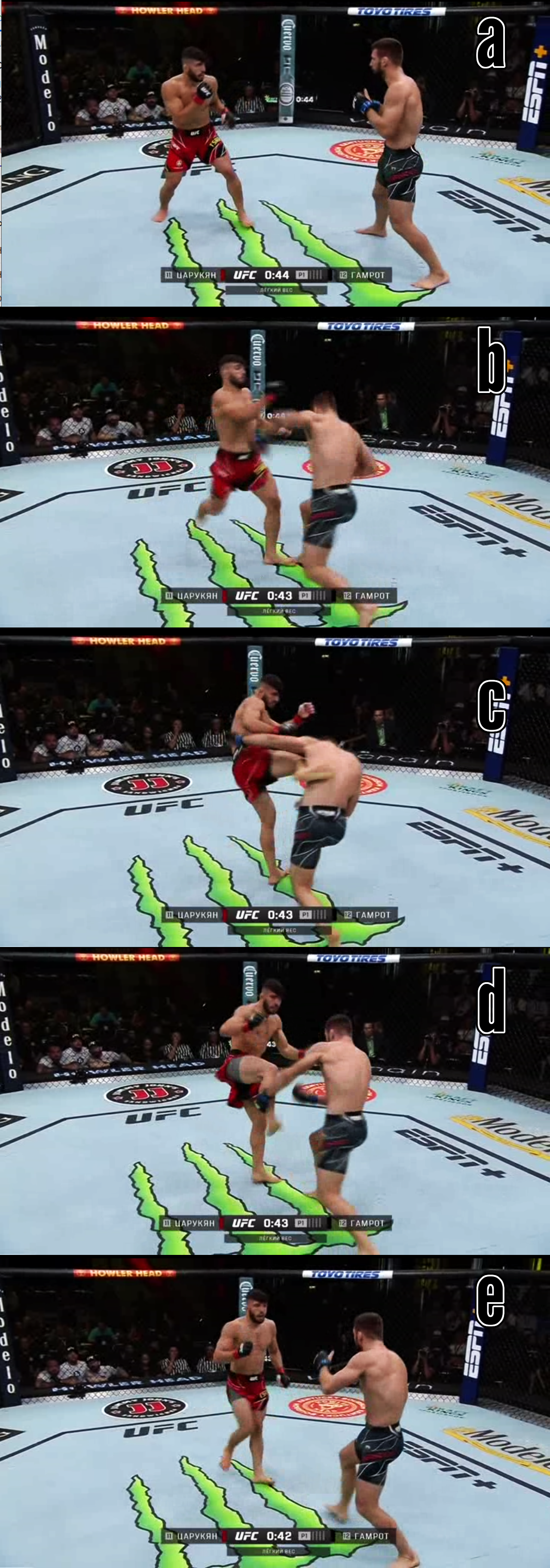

Gamrot, being an elite level fighter, boxes into his takedown attempts. So Tsarukyan reckoned that the best time to kick would be as Gamrot’s hands were away from his body, and as he was committing to a deep step in—intending to get to the legs. Tsarukyan proved to be bang on the mark with this assessment and through the first three rounds he chewed Gamrot up with well timed punts to the ribcage that went in undefended. Figure 2 shows a perfect left footed connection on Gamrot’s exposed ribcage, and Tsarukyan immediately working to fight off the single leg attempt as Gamrot clings to the kick.

Fig. 2

When Gamrot switched to southpaw, Tsarukyan switched from his favoured left kick to a more appropriate right kick to the body, as in Figure 3.

Fig. 3

Switching to southpaw has always been a large part of Gamrot’s striking game because a lot of his most comfortable takedown attempts are performed from a right foot lead. From the first round he was showing the southpaw left straight or overhand into a single leg (Figure 4). You will remember this from Shlemenko vs Mousasi or from Erik Anders’ terrible fight the other weekend. Say what you want about Anders though: he got onto a lot of single legs.

Fig. 4

Arman Tsarukyan stands out for the tailor made counters he breaks out mid fight. Whether his team dissect opponents so well in the film room that they train for this, or he comes up with it in the moment, it was incredible to watch him work out Islam Makhachev and it was equally impressive to see him stump Gamrot through the first three rounds here. After Gamrot had twice attempted the southpaw left straight to single leg, Tsarukyan slipped the next one and went into a head tilt shown in Figure 5.

Fig. 5

Notice that as Gamrot changes level towards Tsarukyan’s lead leg, Tsarukyan stuffs Gamrot’s head to the outside and raises Gamrot’s inside leg to throw him onto his hands. Tsarukyan used this to run to Gamrot’s back.

Returning to the body kicks, there was one more scenario in which Tsarukyan could land them well: when Gamrot pressured Tsarukyan towards the fence. Tsarukyan flattened his stance and side stepped, allowing him to put some power behind his left kick without having to switch or step up first.

Fig. 6

This links in well with Gegard Mousasi’s loss to Johnny Eblen on Friday night. No, really. Eblen fought southpaw and bladed, but when Mousasi pressured him towards the cage, Eblen flattened out his stance, circled right, and then came back with the right hand—now “charged up” by the squaring of Eblen’s body and rebounding off the right foot.

On one attempt of Tsarukyan’s circle off and left kick, Gamrot parried the kick past him and tried to capitalize, only to get knocked down by the spinning backfist just as Joanna Jedrzejczyk had against Zhang Weili.

On last week’s Boicast we gave special attention to Arman Tsarukyan’s scrambly bottom game, particularly the example of using butterfly hooks to elevate his opponent just enough to sit up on single leg attempts. Mateusz Gamrot brings his own unique mash up of wrestling and submission grappling when the fight hits the mat and this could be seen in his use of the Viktor roll (or sometimes “victory roll”) through the first round. This is a sambo leg entry that was made famous by Volk Han in his pro wrestling and MMA runs, but in recent years has become the favourite of one-time Gamrot rival, Garry Tonon.

The Viktor roll used to be seen as a gimmicky technique but there are two factors that have changed it into a legitimate weapon. The first has been the rise of the leg locking game and the greater amount of time that fighters and grapplers are spending in leg entanglements in training. Leg entanglements are now not just finishing positions but sweeping positions and passing positions. The second factor is that while going for a Viktor roll as an attack outright means giving up control to chase some flashy nonsense, there are plenty of positions where using it to get back on the attack beats working purely on the defensive.

Here is a textbook Viktor roll by Garry Tonon against Rahul Raju in ONE Championship. Tonon has Raju pressed to the fence but Raju has the underhook and is almost guaranteed to escape. Instead of trying to push Raju into the fence without the right grips, Tonon turns to straddle Raju’s near leg, reaches through, and rolls into a sweep which lands him in a leg entanglement—ultimately opting to attack the heel hook.

Fig. 7

Gamrot applied the Viktor roll in three different contexts in this fight. The first was probably the most exciting in terms of potential for wider application and can be seen in Figure 8. Tsarukyan has taken Gamrot down and Gamrot has scooted to the fence, so Tsarukyan steps over and locks himself onto Gamrot’s ankles: the classic Khabib position (a). Gamrot scores an elbow to the head and frees one leg (b), placing his hands to the mat and turning his back.

Fig. 8

So far this is a pretty normal occurence. Sitting on the ankles, and the Dagestani handcuff are both techniques that force a fighter to show his back in order to make progress out of a stagnant spot. Yet in (c) you can see that Gamrot shows his back and immediately rolls through his own legs. Figure 9 picks up the action.

Fig. 9

Gamrot reaches back for both of Tsarukyan’s knees and pendulum’s his free leg in order to create momentum to use his trapped leg to carry Tsarukyan over the top of him. This is the same as Roberto ‘Cyborg’ Abreu’s tornado sweep (a, b). As they land, Tsarukyan turns back into Gamrot with a bodylock (c) and Gamrot hip heists up to standing with a whizzer (d,e.)

Figure 10 shows the Viktor roll that Gamrot immediately followed up with. This carried Tsarukyan over the top of him once again, but in the ensuing scramble Gamrot was able to come up onto Tsarukyan’s back.

Fig. 10

One final mention of the Viktor roll and then we’ll move on, but this perhaps best captures the ridiculousness of the scrambling in this bout. Remember that head tilt that Tsarukyan hit to reverse a Gamrot takedown attempt in Figure 5? Figure 11 picks up the action: Gamrot immediately rolls and tries to catch one of Tsarukyan’s legs between his own (a - e). Tsarukyan manages to float over the top and escape his right knee (f), but Gamrot begins coming up onto his back (g).

Fig. 11

A final neat grappling moment came in the fourth round once Gamrot began to have success with his takedowns. Having returned Tsarukyan to the mat with a back bodylock he was in the process of trying to put in his hooks and get on Tsarukyan’s back properly. Tsarukyan was proving tricky. Figure 12 shows how Gamrot chopped out Tsarukyan’s posted hand (a,b) to quickly pull it out and behind his back into the classic hammerlock (c). Ryan Bader was able to attack this against Antonio Rogerio Nogueira. Tsarukyan squirmed free and posted his hand further away from Gamrot to prevent him doing it again (e), so Gamrot used the space between Tsarukyan’s elbow and knee to throw in a hook with his leg and take the back properly.

Fig. 12

It cannot be said enough that this fight was wonderful. The level of the technique was expected to be elite, but it is hard to get your head around the discipline and reaction speed of the fighters to rattle through these exchanges in both the striking and grappling, and for no one to ever really get the upper hand over the full twenty five minutes.

Bautista vs Kelleher

Mario Bautista demonstrated a principle that has become fashionable in grappling in recent years. I used to term this tactic “hopping the head” or just “covering the head” but Gordon Ryan recently released an instructional calling it the “over-the-back grip” and to be honest that’s a better description. In his 2018 No Gi Worlds run, Ryan’s passing was largely of the floating variety, where in his post ADCC 2019 career he has focused more on forcing the half guard and using this over the back grip as a staple.

The crux of the idea is that to move to side control you need to get your body perpendicular to the opponent instead of parallel: by throwing the elbow over their head and pulling them into your armpit, you prevent their head from moving away and lock your upper bodies into perpendicular position regardless of what is going on with your legs. As always when we discuss half guard—the watershed position of grappling—it is all about turning a guard into a pin.

Bautista immediately shot in on a single leg and dumped Kelleher to his rump (Figure 13). Kelleher placed a hand to the mat to begin a getup (c), but Bautista swung his elbow over Kelleher’s head and pulled it into his armpit (d). Even as Kelleher was on one hand, in mid-air, Bautista had effectively locked himself into a cross-body position and ran Kelleher down to the mat.

Fig. 13

Kelleher did a great job of recovering to a butterfly guard and built himself back up to standing along the cage. He did this while holding the head and threatening the guillotine in the style that Ricardo Lamas and Cub Swanson made famous.

Kelleher wound up in bottom position again and wrapped the head to threaten the guillotine (Figure 14). As Kelleher sat back to lock his legs around Bautista and cinch the choke, Bautista switched to a scoop grip inside Kelleher’s left leg (b, c), and then applied that over-the-back grip (d) to pull himself around into side control (e).

Fig. 14

As you can see in frame (b), Kelleher was almost back to closed guard. The issue was that the over the back grip pinned his head to Bautista and removed his ability to move away. At this point, frames (d) and (e), Kelleher’s hopes of getting back to guard are reduced to trying to keep his left knee against his nose. There is no further he can go without clearing that over the back grip.

One last detail from this fight that stood out was that scoop grip on Kelleher’s right leg (Figure 15). We discussed this from side control in Teixeira vs Prochazka but it effectively prevents the bottom man turning to his knees.

Fig. 15

After Bautista passed Kelleher’s guard, Kelleher immediately dug an underhook (a,b)—this was how he had begun his escape back to the feet the first time around. Yet with the underhook from the bottom a fighter is announcing his intention to turn into his opponent, and Bautista underhooking and elevating Kelleher’s leg meant that he could not do that. The moment that Bautista released that leg he knew Kelleher was turning in, so he timed it. He dropped the leg (c) and swung himself into mount (d), (e) as Kelleher turned in. A couple of punches and Kelleher turned his back, right into the rear naked choke.

——————————————————————————————————————

If you’re in the mood for more martial arts technique analysis, check out Combat Jiu Jitsu and Grappling in MMA, my Dustin Poirier Advanced Striking study, and Anderson Silva for good measure. Or keep an eye on the Patreon for the odd Sunday when I feel like writing a UFC post fight breakdown.