Yan vs O’Malley -

Slacky’s Post Fight Notes

The fight between Petr Yan and Sean O’Malley was always going to draw strong reactions, but it was aided by being a close, exciting scrap on a UFC card where sod all else happened. Much of the discord has been over the scorecards and that ultimately comes down to how you weigh the various elements that make up mixed martial arts. In spite of a thousand youtube videos attempting to claim that the judging criteria provide a perfect, objective way to decide a victor in any event, the truth is that it will always be a subjective matter. Rather than re-litigate the scorecards and attempt to give the perfect decision, let us examine some of technical exchanges of the bout because no matter how wrong you think the judges got it, this was a far more competitive fight than most expected.

In the striking portion of the bout, O’Malley’s usual work proved as problematic for Yan as it had been for the lesser fighters he met on the way up. His length, his feints, and his work from both stances all vexed Yan. This was helped along by Yan’s own style because while Yan is a whirling dervish on offence, a good deal of his time is spent walking opponents down behind a high guard. Through much of this fight, Yan walked forward with his forearms up and chin down and was jabbed up. That’ll happen with a high guard, even when you move your head well as Yan was doing, but Yan normally has a better shot at getting back in on his opponent or cracking them on the counter—O’Malley’s build and use of long weapons meant that the opportunities to crack back were not as forthcoming for Yan.

The Car Crash Dynamic

Whenever we preview an O’Malley fight on the Jack Slack Podcast we discuss switch hitting. O’Malley fights from both stances and uses longer, single shot strikes to transition between stances and set up techniques from the new position while his opponent is playing catch up. In Sean O’Malley and the Cross Step we examined this in a little more detail than I intend to go into today. But one way that O’Malley switches his stance is to throw a front kick to the body, and put it down just in front of him, effectively cross stepping himself as he steps out or back with what had been his lead leg. This sets up back stepping counters (as Thomas Almeida ate for the knockout) and can put O’Malley on a line to spin into back kicks.

At some point on the podcast I inevitably advocate for his opponent to switch stances along with him to take his clean, thoughtful hunting from both stances and add a bit of chaos. Yan is a switch hitter himself, albeit not as frequently—and his stance changes had exactly that effect on this bout: it made the fight a car crash.

O’Malley’s best shot in the second round—which stunned Yan—came as both changed stances and O’Malley pitched a left overhand from a closed stance. And then when Yan stunned him in return moments later, it was again off the stance switch.

The ideal is to “be water” and be equally effective off both stances but that is not a reality for anyone, even those who were born ambidextrous. Everyone has their biases and flaws off each stance. Think about Gamrot resetting to orthodox after each trade against Dariush. Coming out of a dangerous, spirited exchange, a fighter will revert to his natural stance momentarily because that is where he feels comfortable under fire.

The element that suffers most during stance switching is a fighter’s defence. When switching stance, a fighter’s brain and defensive reactions can often lag behind his outward appearance. Throwing a rear handed lead at an opponent who is in the same stance as you (closed stance) is considered a sucker’s punch: it has to travel through the line of his lead hand and shoulder, and it has a greater distance to cover than the jab. But if both fighters are floating from stance to stance the “dumb” thing to do can throw the opponent for a loop.

Let’s look at the specific exchanges. Figure 1 shows O’Malley’s great punch at the beginning of round two. He and Yan are both orthodox (a). O’Malley steps his lead foot in and changes level to shoulder feint (b). O’Malley then retreats a full step back into a southpaw stance (c). But Yan withdraws his left foot and advances his right, taking him into a southpaw position as well and returning the fight from an open stance dynamic to a closed stance one (d). O’Malley shoulder feints again (e) but this time—likely because he has just changed stances—Yan falls for it and immediately stretches his hand towards O’Malley’s face to initiate his Jon Jones fingers-in-eyes frame. O’Malley crosses his left hand over the top and catches Yan clean (f).

Fig. 1

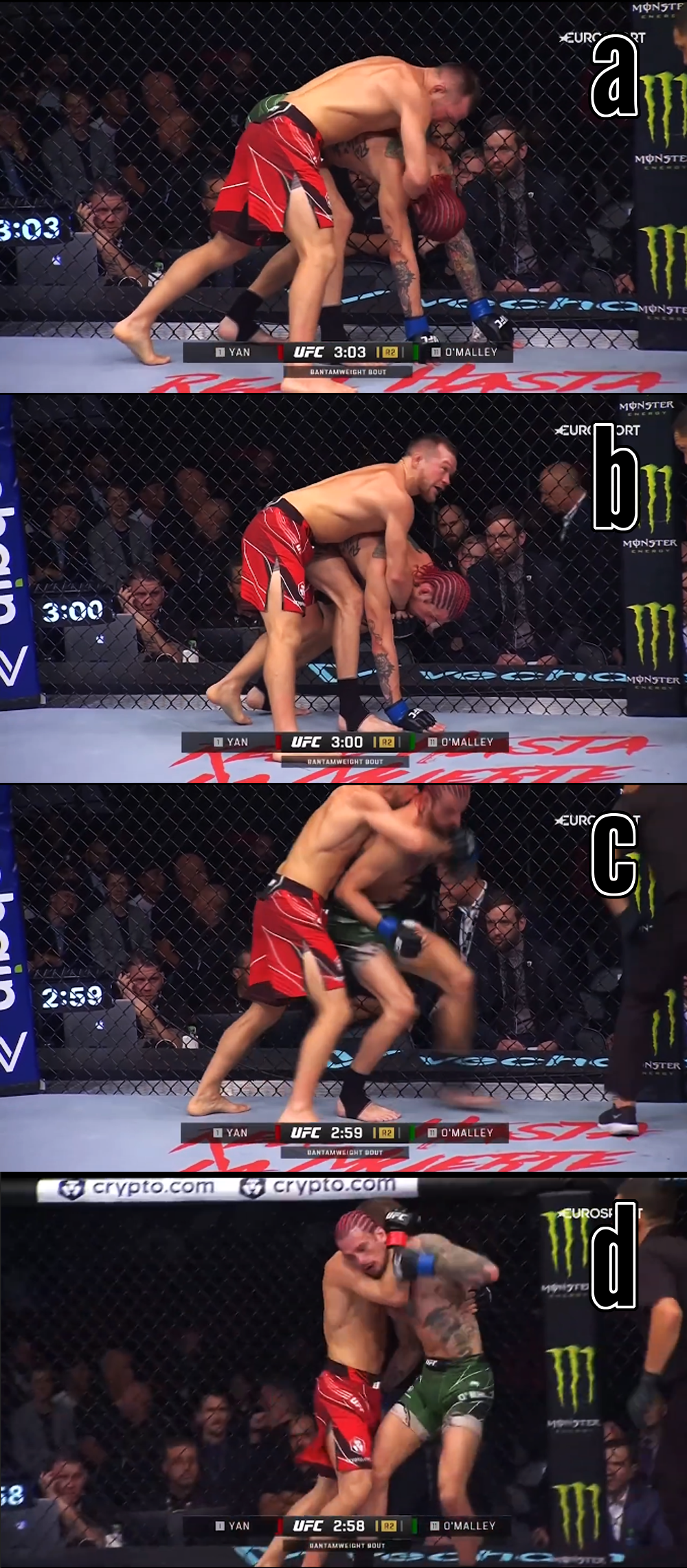

Figure 2 shows Yan recovering from this stumble and turning O’Malley’s head around. O’Malley is pressuring in as a southpaw while Yan is standing orthodox (a), they are both checking the opponent’s lead hand. Yan withdraws his lead leg (b), and advances into a southpaw stance instead, meeting O’Malley’s right hand with his own to create a check on both hands (c). Yan frees his right hand momentarily to score a backhanded jab (d) before pitching an overhand that lands flush (e, f).

Fig. 2

Naked or nearly naked overhands landing on two of the world’s best bantamweight MMA strikers are the sort of things that a boxing purist might poo-poo the fight for—and perhaps the whole sport—but this is the outcome of both men switch hitting. When one fighter is switch hitting, his opportunities and his opponent’s opportunities change as he presents each stance, changing the bout from closed position to open position or vice versa. The trick of it is that in a match between a normal, one-stance fighter and a switch hitter, the switch hitter controls when each set of opportunities is presented. In a fight where both men are switch hitting the opportunities and defences are changing constantly and it creates, as we always say, a car crash of a fight.

The Low Line Side Kick Arms Race

This fight had a hint of the Whittaker - Romero bouts in it, as Sean O’Malley came out and showed the low line side kick in the early going, and Petr Yan thought “I’ll take that.” Yan’s use of the low line side kick was subtle, but it made some of the more interesting exchanges of the fight happen when Yan was struggling to lay his gloves on the taller, rangier O’Malley.

Yan opened the second round with a surprising bit of taekwondo offence (Figure 3): placing a soft but firm side kick on O’Malley’s lead leg (b) to straighten it momentarily and give him time to spring into a right round kick to the body (c, d).

Fig. 3

While the low line side kick is not a glamorous part of Yan’s game and he is more associated with round kicks to the body and big overhands, this side kick set an interesting dynamic in the fight. In the second round, seen in Figure 4, Yan (as a southpaw this time) jumped into the side kick (b) and O’Malley tried to shoot a straight right in answer (c). Yan parried the straight past his head and pitched and overhand in return which O’Malley pulled away from (d).

Fig. 4

Moments later, O’Malley went southpaw and the match up became a closed stance one. Yan stepped up as if to throw the low line side kick but this time placed his foot down behind O’Malley’s and slung him to the mat with that famous Osoto-gari throw.

At the beginning of the third round Yan was able to use the low line side kick to draw that same counter right straight, but this time ducked under it and came up on a single leg. He wasn’t able to complete the takedown but with everything else that was happening in this fight the low line side kick, O’Malley’s answer to it, and Yan’s counter to that counter proved a fascinating vertical slice of the intricacies of both men’s craft.

Fig. 5

O’Malley’s Get Ups

As Yan had trouble landing consistently on the feet, he began to enter clinches and attempt takedowns. Most knowledgeable MMA fans conceded before the fight that O’Malley posed interesting questions on the feet, but it was expected—quite rightly—that Yan’s well-roundedness would prove levels above what O’Malley had faced to that point. This seemed to be true in the first round as Yan cut the cage, scored a kick on the circling O’Malley, and entered on a beautiful shot to come up behind O’Malley in the back bodylock.

The pleasant surprise was that O’Malley’s work to counter the back bodylock throughout the fight was excellent. Figure 6 shows the first time O’Malley conceded this position. He kept his left side to the fence (a), placed his weight forward, and used his right hand to frame on Yan’s inside knee (b). This denied Yan the one truly dangerous strike from this position, so Yan released his grip and scored a couple of right hands (c). O’Malley took these punches to get a cross grip (d), which he could use to get his right hand underneath Yan’s when he tried to return to the back bodylock (e).

Fig. 6

Getting cross wrist control and his other arm underneath of Yan’s gave O’Malley options:

1) The Arm Drag

In A Filthy Casual’s Guide to Petr Yan we discussed Yan’s use of the arm drag from the over under clinch.

Arm drags aren’t all that common in MMA because the distance at which they are most commonly applied in wrestling and grappling—handfighting range—is still striking range in MMA. Rather than using arm drags to enter tie ups and shots, as you would in wrestling, Yan uses them to exit clinches and take an advantageous angle to either re-engage in wrestling or to strike.

In this bout it was O’Malley using the arm drag to throw Yan into the fence as he circled out (Figure 7).

Fig. 7

2) Reclaiming the Underhook

The other option from that cross grip position was for O’Malley to reclaim the underhook and turn to face Yan in an over-under clinch—generally considered a 50/50 position. I believe Dominick Cruz refers to this as “throwing the flag.” Figure 8 shows this technique from that same back bodylock position.

As Yan lands a couple of short punches (a), O’Malley manages to catch Yan’s glove between his shoulder and neck. O’Malley takes the cross grip, this time inside the cuff of Yan’s glove, causing Yan to outwardly appeal to the ref but inwardly respect a fellow cheat (b). O’Malley steps forward with his left foot as he stands upright (c), which gives him space to turn back into Yan and swing his right hand through (d). O’Malley’s right elbow comes inside of Yan’s left elbow and the underhook is achieved.

Fig. 8

Scissor to Turtle

In the first round, Yan completed a takedown along the fence and in spite of O’Malley’s attempts to wall walk, Yan drove his way into inside position and forced a sort of closed guard along the fence. O’Malley used a neat knee shield to turn to the turtle and walked himself back up to the back bodylock position before escaping yet again.

Figure 9 shows the position that Yan had worked his way into (a). I wrote “closed guard” but what I really meant was “inside of O’Malley’s legs.” This is a difficult position to stand from because the legs are shelved on the opponent’s thighs and he is able to put his head against the fence, stack you up and drop punches. Frame (b) shows how O’Malley worked his right shin across Yan’s hip line and tilted himself onto his left side in a scissor sweep style knee shield.

Fig. 9

Picking up the action from a different angle in Figure 10, you can see that O’Malley’s right knee is across Yan’s belly and his left foot is in Yan’s hip. Yan is pushing into O’Malley but being held back by these two checks (a).

Fig. 10

O’Malley replaces his left foot with his right hand on Yan’s hip (b). This frees his left foot, which he intends to suck back under his base, but Yan attempts to hold it. When O’Malley’s leg slips free (c) he is able to prop up on his left elbow and turn into the turtle. His right hand is still inside of Yan’s right and he grabs Yan’s wrist, preventing the body lock as he begins to stand up into that same arm drag / throw the flag double attack.

The three most common get ups you will see from a closed guard along the fence are:

1) baiting the opponent to step over into half guard and then attempting to wrestle up,

2) getting the underhook from closed guard and trying to wall walk, or

3) attempting to wall walk without the underhook—which can get messy.

O’Malley’s knee shield to turtle with the arm left in is a great trick that I will certainly be attempting to steal.

Two other grappling techniques worth noting on O’Malley’s end were the kimura and the switch. The kimura from half guard can be a life line for the bottom player—preventing the opponent from striking effectively by threatening to tear his arm free and apply the submission. In the third round, O’Malley was able to use the kimura to turn from half guard to his knees and continue the same series of break-aways we have already covered.

The switch was a technique that O’Malley was consistently looking for but never completed. It is a favourite of gangly fellows—who can answer a bodylock or single leg by reaching for the inside of their shorter opponent’s thigh from seemingly anywhere. In the third round O’Malley reached for his switch and went to his knees trying to turn back into Yan, but failed to complete, only to turn back the other way and roll over his shoulder into a stand up again.

Fig. 11

Sadly, the brilliance of the fight has been overshadowed by the disagreement over the decision. This has led to trying to work out whether or not the current rules consider top control as a judging criteria equal to striking and grappling or only once those factors are at a stalemate, and so on. The kind of debates that more resemble contract law than film study. Speaking entirely selfishly, I watch MMA to learn things and be entertained. I learned that Sean O’Malley is more legitimate than I gave him credit for, and I was thoroughly entertained.